Co-Cohabitation

++ France is an accident waiting to happen. The European Commission warned its “debt sustainability analysis indicates high risk over the medium term”. It cannot be governed effectively and it faces severely challenging debt/deficit dynamics. There should be a higher risk premium on French assets ++

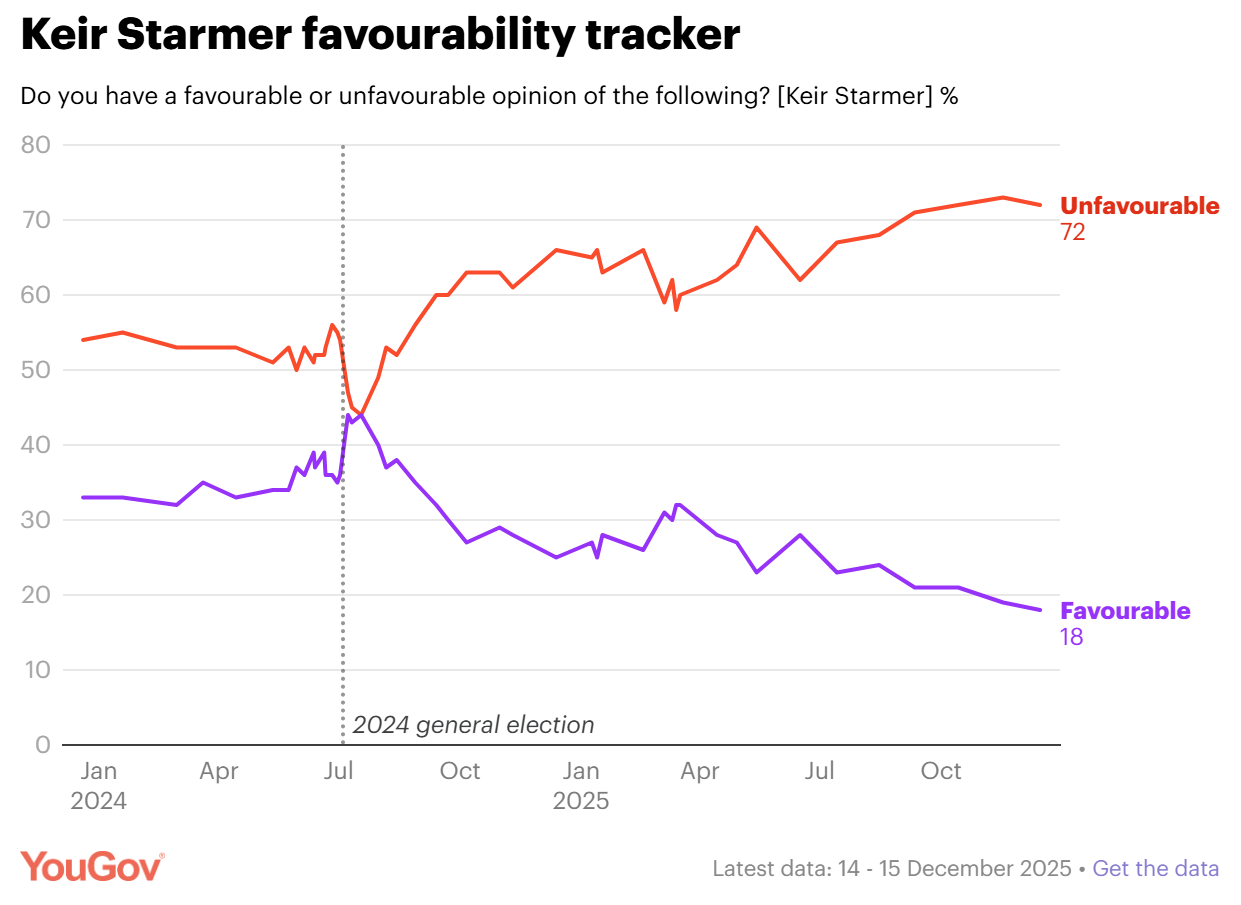

If only forming a government in France were as simple as how Politico puts it in their interactive tool above: “click on a party to form a majority”.

The coloured blocs are only loose formations of separate parties. Many of them are already fracturing. New parties have already been created from the parties within the blocs, such as L’Apres who split from Melenchon’s La France Insoumise. The one coloured group that is a party, “Les Republicains”, has already changed its name and leader since the election result.

And so the simple act of adding up numbers doesn’t determine who will be part of the government.

Pedro Sanchez in Spain is the ultimate example of this. He first took power following the collapse of the Rajoy government despite the fact his party only held 85 seats out of 350; he managed to carry on as PM through three more elections even without holding a majority or even being the largest party. All of which shows that it’s not only the numbers on your side that count: it is also the numbers against you.

This has lulled the market into a false sense of security when it comes to France. Although there is no natural majority to form a government, there is no clear majority against one either. The two blocs at the extremes, the far-left La France Insoumise (LFI) and the far-right Rassemblement National (RN), together only get to 216 seats, below the 289 majority line. And hasn’t Marine Le Pen tweeted that the RN would vote against any government featuring LFI or Ecologist ministers – suggesting that she would not do so if those parties were not involved? Doesn’t that mean that the New Popular Front (NFP) minus LFI plus Macron’s ENS wouldn’t face a vote of no confidence = 275, and Robert est son oncle? This is a premature celebratory calculation.

All of the number crunching misses the point. For a government to work it must have a leader, a mandate, and a platform.

The leader

The French factions can barely agree on their own leader, let alone a leader across groupings. The NFP went into the vote without explicitly nominating a prime ministerial candidate because they knew it would prove so difficult to agree on a name across so many different parties. It is an alliance of more than nine parties, comprising amongst others the French Communist Party, the Ecologists, and the New Anticapitalist Party.

The French political system exacerbates the lack of a centripetal force driving factions together. It focuses power on the President, not the Prime Minister. The President of France is one of the most powerful heads of state in any western democracy and it was deliberately designed that way in 1958 by Charles de Gaulle to avoid the unstable governments of the previous regime. The Prime Minister is secondary, appointed by the President who can dissolve the National Assembly (albeit only once a year). The PM must have the confidence of the Assembly, usually a rubber stamp when the President’s party commands a majority.

If another party holds the majority, there is cohabitation between the President and PM, where both must learn how to work with the other. Cohabitation is relatively rare (it has happened three times before: 1986-88, 1993-95 and 1997-2002) and the Presidential term was shortened to five years after the last of those periods in order to reduce the probability of it taking place. With the President therefore the more powerful position, the PM role is often used as a springboard to the Presidency.

And so the whole system is simply not geared up for putting together a majority behind a unifying candidate for PM. It is top-down, not bottom-up. The unique nature of the current election result can be reflected in the name of the rather random Huguette Bello. She is the president of the regional council of La Reunion in the Indian Ocean – not an immediately obvious CV for the Prime Minister of France. She has been put forward by a number of left wing parties, a reflection of the fact that everyone is trying to find a candidate to support their vision and, more importantly, deny power to someone who does not.

By comparison, Sanchez can knock heads together in Spain because he is the executive within the legislature. The constitutional framework matters.

A mandate

The result of the legislative election is the worst outcome for anyone trying to declare that they have a mandate. Le Pen’s RN won the biggest share of the popular vote, 37%, but her group came third in terms of seats. Almost half of the votes went to the NPF and ENS but at least some of this was an “Anti-RN” vote rather than necessarily a vote for either group’s programme. More MPs were elected on the right than on the left (RN+LR = 190 vs NPF 188) leaving Macron’s centrist Ensemble struggling to decide which way to turn: did the public lean left or right?

Melenchon, ever the instinctive politician, decided to be the first on the wires after the result, claiming the NPF must implement its platform in full and that the President must call on them to govern. The chair of a manufacturing group in the CAC 40 huffed that ‘What got my goat up is that people like me who voted for NFP to block the RN, then had to watch Melenchon claim victory barely five minutes after the polls closed’. Perhaps he should have been careful what he wished for. A vote against something can be claimed as vote for something else.

The NFP can certainly lay claim to a mandate to govern as their grouping came first. The problem is that although they agreed on a common platform they are comprised of very different parties with different ideologies. They are already starting to fall out with one another.

The more that alliances fracture, the harder it will be to demonstrate a mandate. This is where Le Pen is at an advantage. Her group is, so far, very solid, with142 seats. The NFP is more than nine parties; Macron’s Ensemble contains five. The right wing is far more cohesive. The more that the others demonise it, the more that will stiffen its resolve. It will become the more reliable bloc of votes.

To try to bolster the numbers against it, Macron’s first public announcement came in the form of an open letter where he called on: ‘all political forces that recognize themselves in republican institutions, the rule of law, parliamentarianism, a European orientation and the defence of French independence, to engage in a sincere and loyal dialogue to build a solid, necessarily plural, majority for the country’.

He wants what Trichet has called a ‘coalition of ideas’ – a group of centrists of any kind that could pass legislation on a case by case basis. It is not however clear that this exists, particularly not in the numbers required. Macron’s own lieutenants disagree. Outgoing PM Attal claimed that he ‘deeply believed there are forces of the right, centre, and left which can work together in the interest of France’ whereas Interior Minister Darmanin has been calling to govern ‘on the right’. The Republicans have already rejected his overtures. Meanwhile those close to Darmanin have rejected any deal with the left that might include the Ecologistes.

If anyone had a clear mandate, we would know by now. If Macron himself were stronger, he could impose his will. But he has been fatally wounded after two legislative elections where his party lost seats and a presidential election where he only took 38% of registered voters (turnout was the lowest since 1969 and 8% of votes cast were spoilt or blank ballots). If the top of a top-down system doesn’t have a mandate, who does?

A platform

Let us assume that somehow all of the antipathy between MPs, the lack of leaders and the institutional inadequacy to deal with the “none of the above” result were resolved. What would the platform of this coalition of ideas be? Just because you’re on the centre left or centre right, do you agree to an increase in the pension age? What about the minimum wage? How is that determined by a belief in “the rule of law” or “a European orientation”, to borrow Macron’s guiding principles?

It is not.

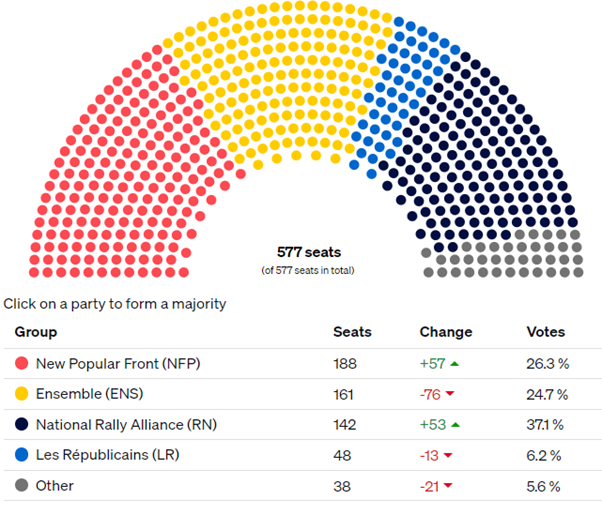

And that’s before we look at the vast challenge facing France today. Its debt/deficit dynamics are horrible (debt to GDP of 110% and a deficit of 5%). It will require tough decisions to put these back onto a sustainable path. It’s the same story in many other nations after the huge debts incurred post-pandemic – and the concomitant lack of growth and low productivity – but it’s not going to be solved by some vague coalition of ideas. It needs a stable government with a strong leader and a clear mandate – Macron must be dreaming of Keir Starmer’s landslide victory.

The markets seem to believe that no government is better than one of far left or far right. But an unsustainable debt/deficit situation is exacerbated by nobody taking any decisions. The European Union has told France that it must make savings of EUR 15bn to get its deficit back down and meet the 3% threshold. Credit ratings agencies had already cut France’s rating before the election result. Such a high debt burden puts the public finances perilously at risk if interest rates should rise.

The ECB might have started to cut rates but, as Greece famously remembers, it’s the local government bond markets that matter. Half of France’s debt is held by foreigners, compared to 28% in Italy.

In the sanguine world in which we currently live, this is interpreted as meaning domestic banks can step up to buy any French debt from which foreign investors might flee. And at what point would the European banking regulators baulk at domestic banks stuffing themselves with a depreciating asset? That’s like saying British banks would have stepped in to buy Gilts when LDI funds were shedding them at speed.

France’s own Court of Auditors just published a report flashing major warning signals on “The Situation and Outlook For the Public Finances”. In short they conclude that 2023 was a very bad year, the 2024 budget path is at risk and long-term goals are unrealistic. They warned that ‘France would benefit from taking the lead and clearly stating, on the basis of more realistic forecasts and credible reforms, how it intends to regain control of its public finances and honour its European commitments’.

The ECB

This isn’t just a problem for France. The EU has had to launch the Excessive Deficit Procedure against them because they are so far from the fiscal rules policing the Stability and Growth Pact which underpins the Euro. The European Commission warned its “debt sustainability analysis indicates high risk over the medium term”.

This has caught the attention of the ECB. Several sources told the FT ahead of this week’s meeting that they are concerned. One ECB rate-setter told them ‘If you know anything about French politics, you know there is no constituency for fiscal consolidation’. Another who ‘declined to be quoted during the “quiet period” in the week before a policy decision’ said ‘You cannot ask smaller countries to respect the EU fiscal rules if the larger countries are not doing so…If they don’t it will be a problem. It makes our job more difficult, because it could push up inflation’.

France is too integral to the European project for its issues to remain within its borders. This isn’t a simple regional issue that can be swept under the carpet.

Expediency

Adding all of this up, we can be sure of the following:

- A weak coalition of the willing will attempt to thrash out legislation slowly, piece by piece

- France’s economic challenges will persist and likely grow

- Pressure will come from bond markets and the European Commission to rectify the worsening debt/deficit dynamics

- Nobody is in charge of France, a co-founder of the EU and G7 economy

In politics, it often requires a crisis to achieve a breakthrough. Clark Kent would never have been elected. Superman, on the other hand, rescues the damsel in distress from a burning building. Counting the numbers of MPs in one group or another today doesn’t reveal who might actually come to the rescue when the time comes.

This is where Le Pen can step in. She already flexed her muscles when the RN backed the contentious immigration and asylum bill in 2023, helping the bill to pass whilst almost a quarter of Macron’s own MPs voted against it. Le Pen trumpeted her influence: ‘Under pressure from National Rally voters, this bill will harden the conditions surrounding immigration. We can salute ideological progress, an ideological victory of the National Rally, because it will now be etched in legislation that there is a national priority’.

This is reminiscent of Sweden in the last few years. In 2018 the right-wing Sweden Democrats became the third largest party in parliament but everyone refused to work with them. A year later, after various prime ministers had been unable to command the confidence of parliament, the leaders of the Christian Democrats and the Moderate Party said they would begin negotiations with the SDs, eventually joining up with them in the 2022 elections as a broad right-wing alliance and pushing Sweden Democrats up into second place with 73 seats. There followed the Tidö Agreement where the SD agreed to a confidence-and-supply agreement with the three other right wing parties. All of this became possible because it had to become possible. Without SD support, the right wing couldn’t pass a budget nor defeat the social democrats.

This is why it is wrong to assume that the RN will have no impact on French legislation. They could team up with any other MPs who want to defeat the government; they could offer their support on bills that match their goals. In this way, they possess a kind of veto power. Their cohesion as a bloc makes them attractive if you absolutely have to get legislation passed.

The Public

And for there to be any government at all, it will need popular legitimacy. Cobbling together a heterogenous group of MPs from various parts of the country is bound to leave many voters feeling disenfranchised. It doesn’t even need to be a majority of voters to cause trouble. The Gilets Jaunes managed to get almost 300,000 people to protest at the height of their powers. That’s a long way from an electorate of 43 million and it did serious damage to the President.

Noise matters more than numbers. The media euphoria at the election result only boosts the narrative that RN voters are so toxic that they must be ignored. If the rest now fail to form a stable government, RN voters might well ask why.

If voters feel that they are unable to express their opinion democratically they will take to other methods. This frustration in the two-party system of the US has already had dramatic consequences.

France should try to form a proper coalition. But co-cohabitation isn’t part of a political system that was designed to create a strong centralised leader and a court beneath him who fight for patronage.

Crises ahead

We are headed for a constitutional crisis. The constitution contained deliberate ambiguity to force President and PM to work together if they should come from different parties. But nowhere did it explain what would happen if the PM didn’t represent a majority.

As this article from Le Monde puts it:

The president is said to have a “reserved domain” in the areas of national defense and foreign affairs. However, the Constitution is far from categorical on this issue. The government “has the administration and the armed forces at its disposal” and “the prime minister is responsible for national defense,” according to articles 20 and 21.

Marine Le Pen already spotted this, warning ahead of the election that aid to Ukraine wasn’t a given as ‘Armed forces chief, for the president, is an honorary title as it’s the prime minister who controls the purse strings’. Maintaining a cohesive ‘coalition of ideas’ around this constitutional tension is something the continent could do without.

There is also the question of whether, or if, the ECB would intervene if pressure in the French bond market were to spread. This is not like the Greek sovereign debt crisis where monetary union forced solvent countries to bail out those that were going bust. Wider French bond spreads would be entirely logical for a highly indebted country without a stable government.

Political unrest in France could spread to other countries. Meloni might feel emboldened by the disrespect meted out to Le Pen, similar to what Meloni herself faced in the aftermath of the latest European elections. The vote on Von Der Leyen to continue for a second term as president of the European Commission takes place on Thursday. It’s a secret ballot.

Meloni’s disgust in the wake of the EU heads of state pre-meeting to choose leaders of the EU institutions was more than apparent. Meloni will want to have her revenge. It’s possible that the core parties in the EU won’t have quite the support they’re banking on and Von Der Leyen won’t be reappointed, or at least by only a thin margin.

Risk is rising

The market remains becalmed, perhaps subdued by summer holidays, low levels of volatility and the onward march of The Magnificent Seven. Nvidia covers all evils! But you can only believe French spreads will narrow if you think it likely a centrist coalition emerges in the next couple of months, passes all budgetary legislation quickly without contention, the French public acquiesces and French growth rises as interest rates fall, lowering the debt and the deficit.

We think the chances of that are vanishingly small. As such, there should be a higher risk premium attached to French assets.