In Reeves We Truss

Just how worried is the Gilt market about increased borrowing by the new Labour government?

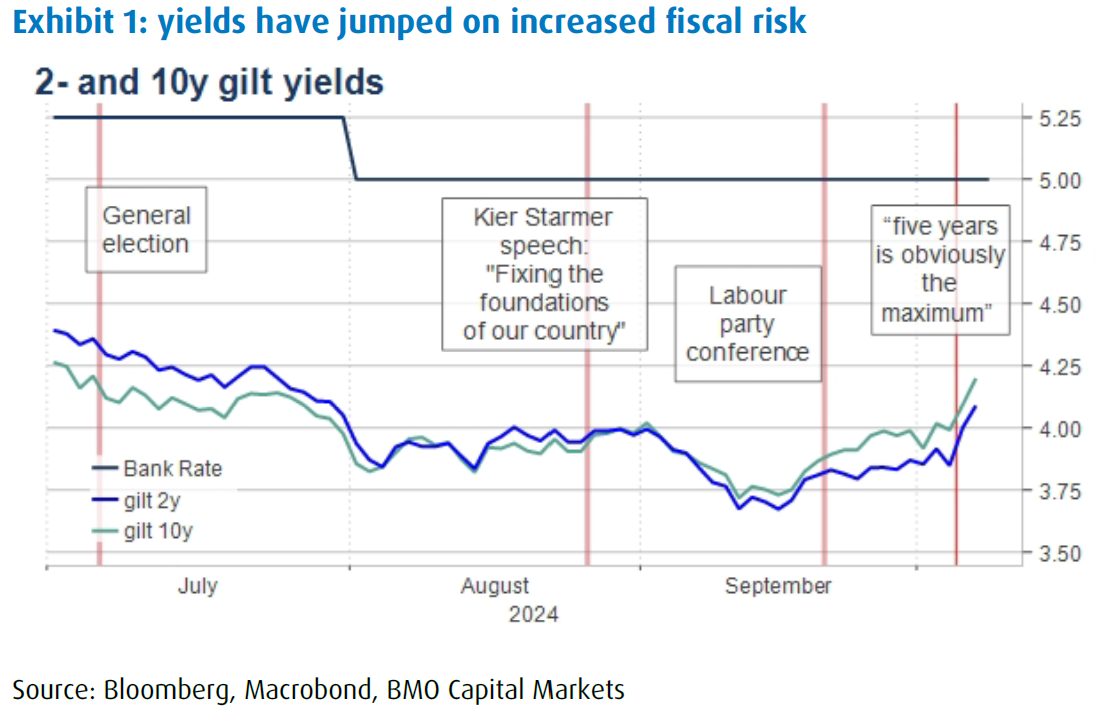

This chart from Simon French of 10 year UK yields versus a G7 average shows that the spread has been widening of late, suggesting there is a UK specific issue behind the rise in 10 year yields:

The FT has been peppered with articles in the last two weeks about how the Chancellor is walking a fiscal ‘tightrope’ and that ‘Gilt investors urge Reeves to keep investment ambitions in check’. They suggest this is a reaction to Reeves’ conference speech exhortation that ‘it is time that the Treasury moved on from just counting the costs of investments, to recognising the benefits too’.

But she already told us months ago that she would be prioritising investment by tweaking the Conservative government’s fiscal rules. In her Mais Lecture of March 2024 she announced:

‘That is why our fiscal rules differ from the government’s. Their borrowing rule, which targets the overall deficit rather than the current deficit, creates a clear incentive to cut investment that will have long-run benefits for short-term gains. I reject that approach, and that is why our borrowing rule targets day-to-day spending. We will prioritise investment within a framework that would get debt falling as a share of GDP over the medium term’.

In this context, the letter to the FT from (amongst others) various economists and former Cabinet Secretary Gus O’Donnell on 16th September which urged changes to the fiscal rules, was simply reiterating her point: ‘In the upcoming Budget it is essential that the government recognises the important role that public investment must play in the decade of national renewal’.

So her focus on investment isn’t anything new. But how to get any investment going when the fiscal rule doesn’t allow much wiggle room for new borrowing? The editorial board of the FT have argued that she could find some space if she changes what is meant by public debt:

But adjusting the definition of the debt shouldn’t be a surprise. Rachel Reeves has already said she is consulting on this, once again in her Mais Lecture: ‘I will also ask the OBR to report on the long-term impact of capital spending decisions. And as Chancellor I will report on wider measures of public sector assets and liabilities at fiscal events, showing how the health of the public balance sheet is bolstered by good investment decisions’.

So what new information have we received in these last 3 weeks that would cause UK yields to rise?

- Public Sector Borrowing is higher than expected

On 20th September it was revealed that the debt to GDP ratio hit 100%, the highest since the 1960s.

But that’s not much of a shock. The borrowing for August was higher than expected at £13.7bn vs £12.4bn – hardly much in the context of the trillion pound debt pile. We will get an update on the latest position on 22nd October but it’s unlikely to affect the OBR’s calculations very much as that is the date of the penultimate forecast round ahead of the Budget:

- The Bank of England was dovish, and then it wasn’t

Andrew Bailey gave a rather curious intervention in his interview with the Guardian where he suggested the Bank could become a “bit more aggressive” on interest rate cuts. The next day the Bank’s Chief Economist, Huw Pill, sounded less keen: ‘it will be important to guard against the risk of cutting rates either too far or too fast’. Megan Greene has also urged caution, advocating ‘a gradual approach to removing restrictiveness’. Gradualism is clearly the name of the game.

When placed alongside the Fed’s punchy 50bp cut and the ECB’s clear need to keep cutting rates, the BOE looks an outlier. That should mean UK rates would be higher than other G7 nations.

- Eagle-eyed Gilt Traders

According to Gilt market veteran Laurence Mutkin in his note for BMO Capital Markets, it all came down to a quote from the FT’s latest interview with Reeves, released on Friday 4th October: ‘she has refused so far to set a timetable for balancing the current budget but said that “five years is obviously the maximum”’. He said this ‘does not exclude the possibility that the current budget will not balance next year’ and that ‘the market took this as unequivocal evidence that the Chancellor’s commitment to fiscal restraint is in doubt, and tanked’.

- Vibes

This feels a little unfair to Rachel. She will balance the budget for day-to-day spending as best she can, prey to the vagaries that life doesn’t always work out according to the forecasts, and she will set out a plan for how to get growth in the long term, by reducing uncertainty and beefing up investment. Why isn’t she being given the benefit of the doubt?

It’s the small matter of time and messaging. By ensuring the OBR would have the full 10 weeks they require for the forecast rounds ahead of the Budget, she couldn’t hold the big event much sooner, not least with party conference season hoovering up time. Liz Truss tried to jettison the process and look how that ended up. But in the time taken between the historic election victory of 4th July and 30th October, a vacuum has opened up. And it has been filled with Free Gear Keir, the defenestration of the Chief Meme of Staff, Sue Gray, and temporary Downing Street passes for a Labour Lord. If it has been about economics at all, then it’s been doom and gloom fiscal black holes and the removal of the winter fuel payment. Even the normally adroit communicator Wes Streeting was left parroting about extending hardship support and the triple lock on pensions when asked repeatedly and simply by Newsnight’s Victoria Derbyshire “what’s your advice to pensioners who are frightened about the forthcoming winter?”. She pointedly concluded the interview with “Pensioners, come on, £1.4bn of saving in an economy of a trillion?’, which he feebly tries to correct to “against a black hole of £22bn”.

Because that’s all he can say right now. All he has got to go on is Reeves rushed first announcement before the recess, where she decided to settle the public sector pay strikes ASAP and grab something to make her look tough and bring in revenue on the other side of the balance sheet. As we warned in “Rachel Reeves: Starts As She Means To Go On” ‘perhaps now that she’s started, she shouldn’t wait three months to finish’.

- Borrowing is the only lever left

In the vacuum, we are left with a dawning realisation: all of her attempts to bring in revenues are too small to be significant (note the watering down of changes to non-dom rules, the compromise on private equity carried interest, even the legal and administrative challenges to VAT on school fees) and her investment goals are too large to come from current growth alone. The balance will have to fall on borrowing.

But how much more borrowing is too much for the market to digest? Is it OK to adjust the definition of debt to create space for £53bn or only for £16bn? The IFS Green Budget Spending Review warned that just keeping the same departmental spending has a quantum that ‘Under reasonable assumptions, the required top-up could easily run into the tens of billions’. This is where political decisions must be made:

Does it even come down to a number? The whole plan must be credible, not just the numbers in a particular cell of the spreadsheet. The IFS chided ‘ if the government wants to relax its debt rule to allow for more borrowing for investment, it is not enough to justify this on the grounds that ‘investment is good’. It also needs to explain why we should be borrowing to pay for it… it should make the case for this explicitly, rather than hiding behind a ‘technical’ change’.

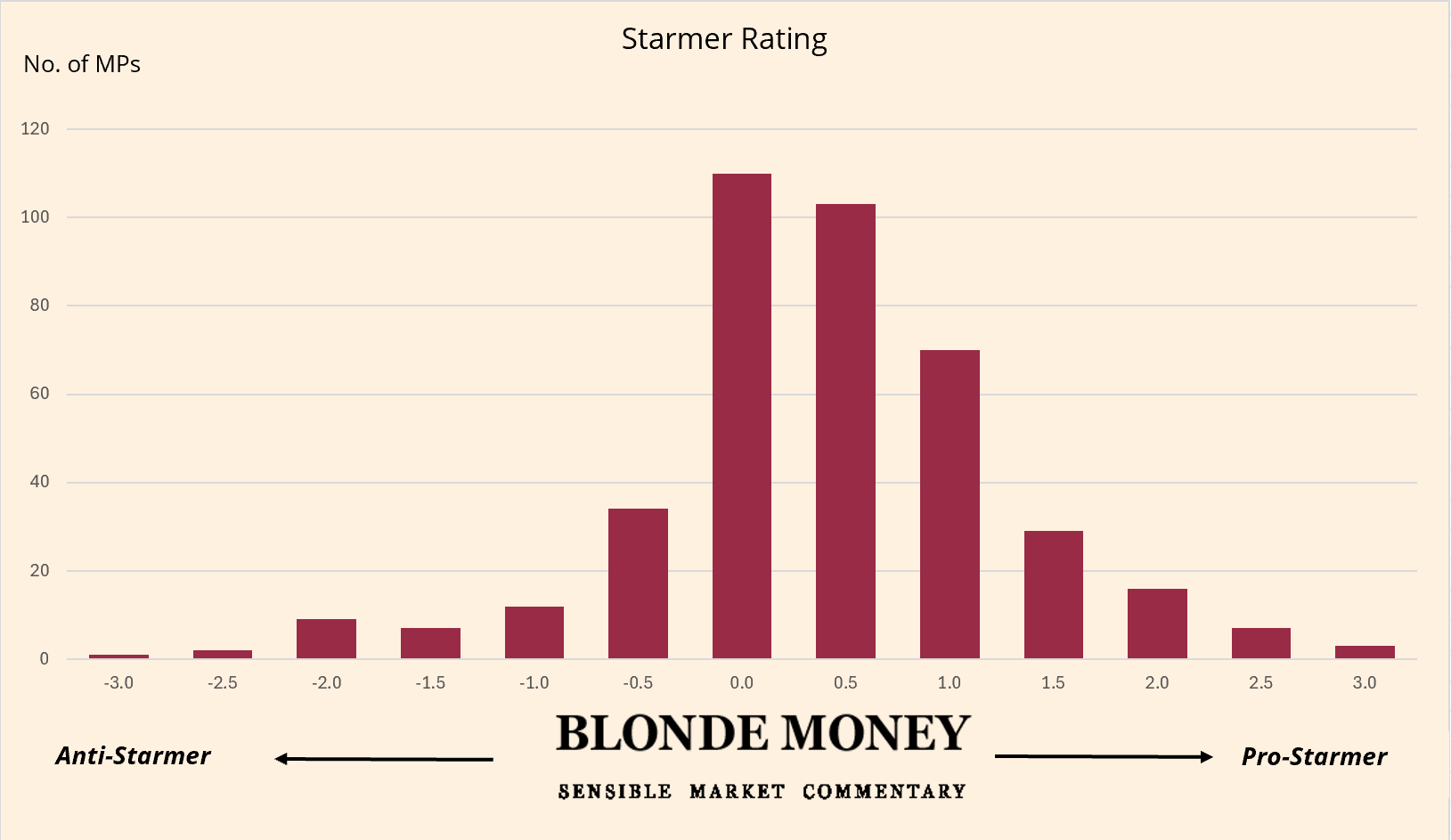

You would think a newly elected government with a huge majority and a Chancellor who used to work at the Bank of England wouldn’t need to worry too much about credibility. But the political wobbles of the first 100 days, from the Labour leadership losing a vote at its own conference (against the cut to the winter fuel payment) to the removal of the PM’s own chief of staff because, in her words, she ‘risked becoming a distraction’, have created nervousness. If the backlash to just one policy, which the Treasury policy paper calculated would only raise £1.4bn, is so extreme then what will happen when the whole Budget reveals the true horror of tough choices? Reeves knows that it is by taking the tough choices that the markets will be reassured of her credibility. In effect, she is choosing the markets over her party – the exact opposite of Liz Truss. This is sensible. Reeves has the large majority and five years until the next election. Take the tough political decisions now, gain credibility, and the market will allow her to invest for growth.

She said in her conference speech ‘We were elected because, for the first time in almost two decades, people looked at us – looked at me – and decided that Labour could be trusted with their money’. And all eyes will be on her at the despatch box on 30th October.

Unfortunately for her, she has to remain quiet until then, leaving the markets to worry about what she hasn’t said. We are getting a back up in 10 year yields on the mere fear of something that the market should already have been aware of. It won’t take much to generate more of a wobble. An FT headline could itself become a story. But the story is not the truth until Budget Day.

Fortunately for Rachel, the wobbles are likely to happen before she stands up. She can then adjust the spreadsheet so that she doesn’t frighten the horses. Sell the rumour, buy the fact, as the likelihood is that Gilts will sell off beforehand creating a feedback loop that pushes her to become more fiscally prudent on the day.