The Year That Will Be 2025

Last year we told you the UK election would happen sooner than you thought; that Trump would win; that Germany would call an early election; and that global conflict would heat up.

This is the year where politics and financial markets collide. Forget business cycles or basis points on economic data. Something much bigger is happening after the huge changes of the last five years.

We had the crisis. We had the response. We had the recovery.

Now we have the reckoning.

It is five years since a mysterious new disease emerged from China. The period has seen big winners – and big losers. It’s seen our way of life inexorably changed. There is no “back to normal”. It would be weird if there were. Imagine if you told your teenage self: they locked us all up, war broke out, food prices went through the roof, all questions can be answered with AI and we have friends we have never – and will never – physically meet. This is the Technological Revolution with war, pestilence and famine. No wonder social media is full of cat videos. Occupying ourselves with the really big questions appears too difficult when the answers feel so far from our grasp.

People despair of the polarisation that comes from shouting at one another in the internet void. But it is a necessary process to debate one another, try one path, fail, then try another, before settling upon the new way forward. Wars have been fought over the assassination of archdukes; a war of words over the size of the state is the least we should expect after government literally dictated our movements.

Survival to this point required such a huge stimulus that the state racked up massive amounts of debt. Inefficiencies wrought by the shift to a new economic paradigm raised inflation, compounded by geopolitical conflict, and interest rates rose concomitantly. So where do we go next in this high-debt, high-inflation, high-interest rate world?

This is where politics comes in. We have had the monetary response. Fiscal decisions lie with the politicians. As they should – because it redistributes wealth. Choices must be made. Now, after last year’s mammoth raft of elections, changes are happening.

With so much debt to digest, the market is reassessing who can pay their way. Governments with a mandate to deliver a plan the market considers to be credible can escape from the debt straitjacket; if not, the country is doomed to remain shackled.

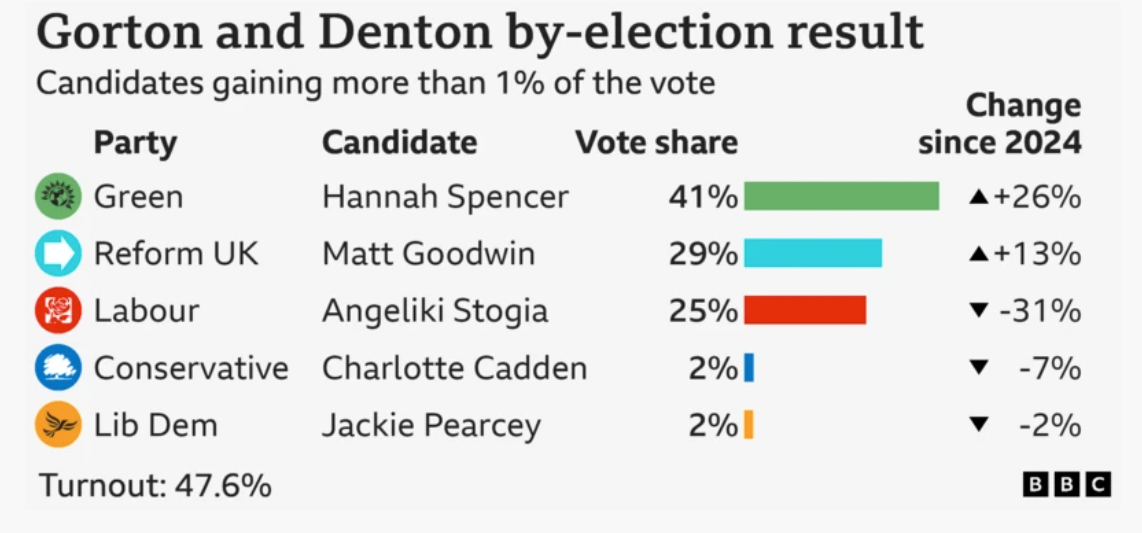

But policies that please the market are unlikely to please all, or even the majority of, voters. The huge economic and social change of not just the last five years, but the period since the financial crisis, have left the electorate fragmented. It is no longer possible to win an election from the centre because voters are migrating to the extremes. The old system didn’t work for many of them and they are looking for radical new solutions.

This has created unstable governments who falter under the weight of their inconsistencies, such as the collapse of Germany’s first post-war three-party coalition. The SPD, the Greens and the FDP decided to join together despite fundamentally opposing views on Germany’s debt brake. It could survive during the recovery but not the reckoning. Everyone agrees to work together during the storm but an unbalanced and unequal life after the clean-up brings tensions to the fore.

- A three-party grand coalition of CDU/CSU, SPD and Greens will try to govern Germany in the aftermath of the February election but it will ultimately fail and the AfD will have an input

The less proportional an electoral system, the greater the stability should be. For example, with a First-Past-the-Post system such as that of the UK, an electorate split four ways (left v right and authoritarian v libertarian) can deliver a huge majority if one party takes just 25% + 1 vote. Compare this to France where it’s becoming impossible to govern by ignoring the 30% of the electorate who prefer Le Pen’s National Rally. Macron needs the bond vigilantes to kill the government now rather than torture him into ignominy.

- France to have two elections this year: National Assembly as soon as possible given budgetary impasse and Presidential once Macron resigns. Le Pen will win the latter and National Rally will form the government.

And yet the UK’s debt market is bedevilled by as much, if not more, concern than that of France. Partly this is due to sticky inflation leaving the Bank of England in an invidious position whereas the ECB can slash rates with impunity. The straitjacket of Debt-to-GDP over 100% is marginally easier with lower interest rates.

But it is also because a government with a majority isn’t simply enough. For a government to deliver a credible plan, it must have a mandate. The Labour Party broke the implicit contract with their voters by, in its first fiscal decisions, removing benefits from pensioners and taxing jobs. This was supposed to be a stable government that would deliver growth through investment in public services, not what can be described as an evil granny-killer hiking costs for businesses. Blaming it on a black hole didn’t do much for sentiment with a weary public either. They already knew it was bad – that’s why they voted for change in the first place. The change so far seems to be the same as the previous lot, tax hikes and spending cuts, but from people you thought were too moral do it.

- Rachel Reeves will not deliver another Autumn Budget

- Starmer will face a leadership challenge into the party conference but survive

- The Labour Party will informally split under market pressure to accept spending cuts that are considered existentially unpalatable by many of its MPs

- Reform will consistently top opinion polls

By comparison, Trump and the MAGA Republicans won the popular vote and control all three branches of government on a mandate of tax cuts, border controls and tariffs. DJT v2.0 is doing Truss with a reserve currency. Whether you think it will work depends on your economic ideology. But it does mean we can be sure he will be going for growth.

He’s going big or going home. Not for him cutting £4m of spending on Latin in secondary schools. He’s talking about buying countries. He will be 82 by the end of his term. In just a few days he will have signed a flurry of executive orders on tariffs; deportations begin; regulations will be ripped up; and legislation to extend tax cuts will be laid in Congress.

He will also change the shape of geopolitics. He will shake up post-war institutions that he no longer thinks are fit for purpose, like NATO. The world has to dance to America’s tune. If not, you won’t be dealing with the world’s largest economy. You’re either with America, or you’re against it. His approach could peel off countries from the BRICS, leaving the BRCs or the RIBs.

It will be a multi round game. More jaw jaw, less war war. Trump has and is willing to use his arsenal which is not necessarily cruise missiles. Tariffs can be raised or lowered, countries can be brought in or kicked out of trade areas, regulations can be slapped on foes and reduced for friends. Imagine the CEO of a company who can write his own laws.

It doesn’t mean Trump will get everything he wants. But it does mean there’s going to be far more volatility than previous years as the world adjusts. We often say that business is about what works and politics is about what sells. Something eminently reasonable to a businessman is anathema to a high school teacher in Idaho – and vice versa. This means the market must broaden its expectations of what is politically possible. Although US equities should benefit from all the capital flooding into what will be sold as a businessman’s utopia, the Sharpe Ratio of the S&P500 will be far lower than it was in the last two years.

- The VIX will be above 20 more than it is below 15

- The MAG7 will become The MAG493 as the rest of American companies catch up

- Bitcoin to soar as Crypto goes mainstream

- The US will win the ugly contest in bonds