The Two Weeks That Will Be

1. The US

The Tariff Man is back. Trump did suggest on inauguration day that he would impose tariffs from 1st Feb on Mexico and Canada and lo and behold he has. Eleven days was never going to have been enough time for either country to take measures to avoid the tariffs but what the market interpreted as a delay did mean Trump could bask in the glow of a stock market rally to greet his installation in the Oval Office. Now he will have to suffer what he admitted in his Truth Social post might be “some pain” but “IT WILL ALL BE WORTH THE PRICE THAT MUST BE PAID” (his caps, obvs).

Although markets have adopted the heuristic of “tariffs=bad”, the economic reality is more complicated. They can be inflationary if passed on to consumers, or deflationary if other countries undercut to offer substitute imports. Their persistence depends on tit-for-tat responses and even though Canada and Mexico have retaliated, it is not all in one go. Canada will impose tariffs on CAD 30bn of goods from Tuesday and the remaining CAD 125bn in twenty-one days; Mexico hasn’t yet revealed its hand but sources familiar suggested the auto industry would be exempted. China announced it is going to file a complaint with the WTO and take as-yet-unspecified “corresponding countermeasures”. Trump could, in a future round of the game, remove tariffs. Sure it might cost him $200 but if it costs you $1,000 then he can sustain the position until you give in.

Part of the market’s pejorative Pavlovian response to tariffs comes from the almost two-decade long experience that higher inflation = higher interest rates = bad. But what if Trump does indeed reflate the US economy with tax cuts, spending cuts and deregulation? The US might happily sit as an economy with the trifecta of higher inflation, higher interest rates and higher growth. The post financial crisis perma-QE deflationary doom has held a long grip on investors. But we are in a new era. It might work.

Except that with such huge levels of debt-to-GDP, it also might not. Trump is Truss with a reserve currency but investors are struggling to digest all the debt on offer. Trump is gambling that right now, at his most powerful, in the wake of a big election victory that granted a mandate for MAGA-reflation, he has to go for growth. The latest US Treasury Refunding Announcement comes on Wednesday.

Tariffs are part of his game of power. With almost all of his adversaries struggling with high debt and low growth, he wants to steal a march. He also has the political advantage. Justin Trudeau might have been the person at the lectern announcing Canada’s retaliation but he is already a footnote in political history. China’s leadership might be technically unassailable but there is trouble at t’ mill of China’s bursting bubble property market.

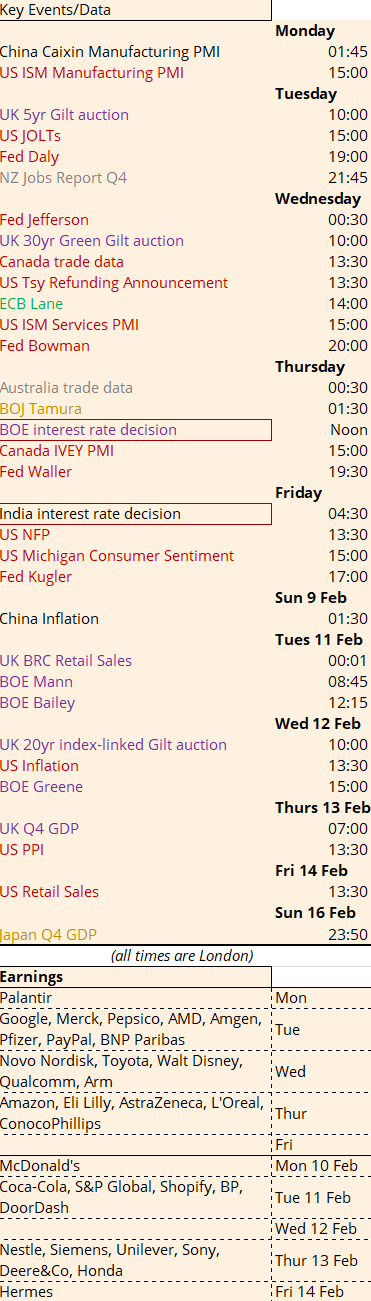

It does rather render as moot the upcoming US inflation print on Wednesday 12 February. More relevant for the current state of the US economy will be the bellwether ISM on Monday and Payrolls on Friday. The latter will be more important than usual given it will include the annual benchmark revisions. Provisional estimates showed there were 818,000 fewer jobs added in the year to March, which was then itself revised up to 668,000 fewer. These are big swings, partly driven by immigration flows. The US Census Bureau recently updated its methodology to calculate that a net 2.8 million people migrated to the US between 2023 and 2024:

With immigration such a hot political topic, we can expect a flurry of Trump tweets in the aftermath.

2. Germany

Immigration has shot up to the top of the list of what is on German voters’ minds as they enter the three weeks before election day, with the topic jumping 14 points in a month:

A spate of violent attacks by asylum seekers has played its part. The latest, where a toddler was tragically stabbed and killed by a 28 year old who had his asylum claim rejected and was due to return to Afghanistan, has pushed CDU leader Friedrich Merz to break the taboo of working with the far-right AfD. Merz managed to pass a (non-binding) vote on tighter immigration measures with their help, although the subsequent binding legislation was rejected by a margin of 11 after 12 of Merz’s own CDU MPs failed to vote. Angela Merkel had intervened with a public statement the day before, where she quoted Merz’s promise of 13 November that the party would never allow the AfD to pass a majority measure, reminding him ‘This proposal and the attitude associated with it were an expression of great state political responsibility, which I fully support. I think it is wrong to no longer feel bound by this proposal and thereby knowingly allow the AfD to gain a majority in a vote in the German Bundestag on January 29, 2025 for the first time’. The Catholic and Protestant Churches of Germany wrote a joint letter to parliament ahead of the vote, warning ‘We fear that German democracy will suffer massive damage if this political promise is abandoned‘.

And yet Merz went ahead and did it anyway. He is gambling that the public would rather vote for him to get tough on immigration than the AfD, who have been gaining ground on his party in recent polls. It’s only a couple of percentage points but Merz wants as strong a hand as possible in coalition negotiations.

The problem is that his stance will make it harder for the SPD and the Greens to work with him, if a grand coalition can indeed even find a way to make an agreement. The vitriol between the SPD, Greens and CDU has been coming thick and fast. Habeck warned Merz not to pivot to the AfD, “Don’t do it Mr Merz…[it would] destroy Europe“; Merz told Habeck “you are the federal minister of economics in the fourth-largest economy in the world. People want to know more than how they can replace their refrigerators and how they can get a heat pump into their cellar… I can only say to you, have a good journey with your proposals and then look for a coalition partner who will go along with them. No way will you be able to do this economic policy with us”.

We can only agree with Habeck:”There are no guarantees that we will get back to a quick and smooth government after the new election“. The risk premium on German assets will persist for some time to come.

3. The UK

The same is true of the UK, even after a landslide victory for the UK Labour Party. Their majority came with very little mandate, scared as they were by the suicidal impact of Liz Truss’ attempts to change the country’s direction with no mandate at all. The pledge for no taxes on working people alongside a slavish genuflection at the institutional altar of the OBR has left Rachel Reeves pursuing policies that even her own MPs aren’t too sure about. They understood difficult decisions would have to be made but it’s an uncomfortable step from punishing those inheriting wealth to taxing jobs and expanding airports.

It’s even more uncomfortable when it doesn’t seem to stack up to any kind of strategy. Paul Johnson, the Director of the IFS, wrote in The Times “What is this government’s theory of growth? Nobody knows”, explaining that “if there is no guiding philosophy it is hard for ministers and civil servants to have a sense of which way the prime minister or chancellor will swing when it comes to any individual decision… It also leaves businesses uncertain as to the future direction of policy”. The markets have certainly evinced a resoundingly sceptical response to his question “Will a government that increased taxes a lot, and spending even more, in its first budget really shy away from further tax rises and be ultra-tight on public spending from now on?”.

Politicians often argue they should be judged on their actions not their words. When it comes to a third runway at Heathrow, Frontier Economics calculated it would add 0.43% per year to GDP growth by 2050. That’s ephemeral to a voter today when they just lost their winter fuel allowance or if they’re facing an increase to NICs in two months’ time.

Voters weren’t the target audience for much of Reeves’ growth speech. The OBR starts its first forecast round on Tuesday 4 February. Given their last forecast included a 75 year chart for growth, those Heathrow benefits for 25 years’ time look relatively timely. Convincing the OBR to add a couple of basis points to growth by the end of the current parliament will buy some fiscal headroom. Reeves reiterated in her speech that the fiscal rules “will always be met”.

Except that the updated “Charter for Budget Responsibility” confirms that the OBR only judges ‘whether the fiscal policy set at that Budget is consistent with a greater than 50 % chance of achieving or exceeding the fiscal mandate‘. And it’s not simply up to the OBR. The market is constantly making its own judgements. One Gilt market sell off and the OBR’s judgement is redundant. Over time, the OBR’s forecasts themselves become out of date. On Thursday 13 February we get the UK Q4 GDP reading. Having lurked close to zero for the past few quarters, Reeves will find herself under pressure if a simple basis point pushes it into negative territory. You can imagine the headlines screaming of a recession.

Reeves has tied her hands with her persistent argument, emphasised in her growth speech, that ‘economic stability is the precondition for economic growth‘. This echoed her Mais Lecture theory where she argued people can only take risk when they feel secure:

- ‘Now you might ask: doesn’t ‘economic security’ imply a denial of ‘risk’, the motor of innovation and entrepreneurship?… When change increasingly appears disruptive and the future darkly uncertain, there is a natural urge to recoil from change.. Securonomics is about providing the platform from which to take risks… To know that people can stand and fall on their own merits, not on the basis of events far beyond their control‘.

Perhaps it is just as well that there are only 11 Bloomberg terminal subscriptions in The Treasury, otherwise they would be poring over each new UK data release and every basis point shift in UK yields, rendered apparently powerless to do anything until the OBR tells them the final numbers on 26th March. They don’t need a Bloomberg to tell them appetite for Gilts however, with the DMO conducting three Gilt auctions in the next two weeks: 5yr on Tuesday, 30yr Green Gilts on Wednesday and 20yr index-linked on Wednesday 12 February.

The Bank of England will provide some help for growth when they cut interest rates on Thursday. They should have done so in December. Now they will deliver a 50bp cut and signal more to come if activity remains weak. It will be a close vote, which hawks such as Catherine Mann will not back. She can explain her thoughts in a speech on Tuesday 11 February. On the same day, Governor Bailey speaks on the surprisingly esoteric topic of “Are we underestimating changes in financial markets?”. Megan Greene will explain her vote on Wednesday 12 February. Scepticism from the hawks and sticky UK inflation will see the UK yield curve steepen which will cause a further headache for Reeves’ ability to meet her end-of-parliament fiscal rule if the 5 year portion of the curve comes under particular pressure.

But it’s not just an issue for Reeves. The political rather than economic room for manoeuvre for a Labour Party languishing in the polls is limited. You don’t need a Bloomberg terminal to tell you that.

4. Norway

The UK’s political system should have rendered the Labour Party unstoppable, as it has for Trump. First-past-the-post systems exaggerate the power of the winner, unlike more proportional systems where coalitions must be formed. At a time of fracturing electorates, stretching out to the extremes, coalitions become unstable. Another has collapsed, this time in Norway, where the Centre Party exited, leaving the Labour Party to govern alone. The leader of the Centre Party had been the Finance Minister, and he issued a statement on “The Fight for Low and Stable Energy Prices”, complaining he could not accept the EU’s fourth energy market package. He vowed to “take back national control“. He also blamed previous conservative governments for exacerbating price rises by allowing the construction of two new undersea power lines to Germany and the UK.

Old alliances are fracturing, allowing new ones to be redrawn. Trump is bounding into this fluid state of affairs, forcing countries to pick a side and be rewarded and punished as he sees fit. Rachel Reeves appears to agree, having spotted this in her Mais Lecture: ‘in a more dangerous world, we must be clear-eyed about where trade-offs exist, and strategic about the directions in which we choose to deepen our economic relationships’. It remains to be seen if the UK can face both China and America.

5. Earnings

In the midst of the geopolitical hullaballoo, some real companies are releasing real earnings. The recent volatility in Nvidia’s share price is just the first salvo in what will be a far more volatile year for stock markets. We will be watching releases from some big consumer, healthcare and tech bellwethers:

- Tuesday: Google

- Wednesday: Novo Nordisk, Walt Disney

- Thursday: Amazon

- Monday 10 Feb: McDonald’s

- Tuesday 11 Feb: Coca-Cola, DoorDash

- Thursday 13 Feb: Unilever