Trade War

There are two different events taking place. One is the deliberate jolt of the global trading architecture, the other is the inevitable de-leveraging of an overly complacent financial market. Each feeds into the other. On top lies a media driven by clicks and eyeballs along with a layer of unconscious political bias by those who consume it. Financial market professionals are not immune, having benefited from decades of consensus about the unyielding supremacy of the Fed Put.

So what is really going on?

1. The New World Order

The tariffs are not purely economic. The headline of the official White House statement released on 2nd April 2025 explained the purpose of the tariffs, all in caps: “PURSUING RECIPROCITY TO REBUILD THE ECONOMY AND RESTORE NATIONAL AND ECONOMIC SECURITY”. It goes on to say that ‘Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits have’ [amongst other things] ‘rendered our defense-industrial base dependent on foreign adversaries’. This echoes the article written by Scott Bessent for The Economist last October entitled ‘how the international economic system should change’. He warned that ‘integration with rivals, such as China, has created vulnerabilities’. Trading partners need to be a reliable part of the US defence system. In exchange they can benefit from coming under the cover of the US defence umbrella.

This is why the tariff statement explained that the president can ‘decrease the tariffs if trading partners take significant steps to remedy non-reciprocal trade arrangements and align with the United States on economic and national security matters‘. It is not simply a zero-for-zero tariff calculation. Non-tariff barriers such as regulations must change and, at least as importantly, the country must ‘align‘with the US on national security.

For the Make America Great Again faithful this ties into one clear narrative: the US lost industrial jobs to China, hollowing out its manufacturing base and leaving the country vulnerable to the removal of key elements of their supply chain. By bringing manufacturing capability back onshore to America, rust belt factory workers hope to get their jobs back and at the same time the country can secure greater capacity for its defence. The 2nd April tariff statement made this connection explicit, noting:

‘U.S. stockpiles of military goods are too low to be compatible with U.S. national defense interests.

- If the U.S. wishes to maintain an effective security umbrella to defend its citizens and homeland, as well as allies and partners, it needs to have a large upstream manufacturing and goods-producing ecosystem.

- This includes developing new manufacturing technologies in critical sectors like bio-manufacturing, batteries, and microelectronics to support defense needs.

The tariff structure had to cover as many countries as possible, to give them a choice whether they become an ally or not. As Bessent explained in his article, ‘the cost to remaining outside the perimeter would be high’. On the inside, you’re protected by the huge defence capabilities of the US and able to participate in US markets. If you’re on the outside, in Bessent’s opinion, you are vulnerable: ‘Chinese overcapacity would instead threaten the viability of other countries’ domestic output. And would-be hegemons outside the US-led zone are unlikely to prove as benevolent as the United States in the post-war era’.

We have already seen former WTO chief Pascal Lamy point out that the EU has anti-dumping and anti-subsidy measures to prevent China dumping their over capacity of cheap goods onto the EU.

Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, Steve Miran, gave a speech to the Hudson Institute where he admitted ‘I’m an economist and not a military strategist, so I’ll dwell more on trade than on defense, but the two are deeply connected’. He goes on to talk of being part of the American defense and economic umbrella as being a “global public good”. He argues ‘our financial dominance comes at a cost… Others may buy our assets to manipulate their own currency to keep their exports cheap’. He wants to rebalance the equation and force countries to share in the burden as well as the benefits. He makes five suggestions for how to share the burden:

- Accept tariffs without retaliation

- Stop unfair trade practices and buy more from America

- Boost defence spending from the US

- Make products in America

- Write a cheque to the US Treasury

More specifically, he has suggested, in the ever-more-infamous ‘Mar-A-Lago Accord’ paper that he wrote before taking office, such options as charging a fee to hold US Treasuries, forcing investors to term out their Treasury debt and accumulating foreign currency reserves.

2. The Systemic Crisis

So we have a Trade War that could become a Currency War and a deliberate plan to redraw the use of the US financial system. Such a shock would have a significant impact at the best of times but we are in a post-Covid era where risky asset prices have gone ever upwards whilst volatility remained extremely benign. The Pavlovian response to buy every dip, always be fully invested and expect the Fed to backstop any disaster was a rising tide that lifted all boats. This was deliberate in the aftermath of a potential economic depression alongside the health emergency of Covid. It deliberately removed the far left tail of negative outcomes. But it stopped people from owning insurance against downside as it became a drag on performance, given it expired worthless. With a Sharpe Ratio of 2 on the S&P500, why think any further than buying the index?

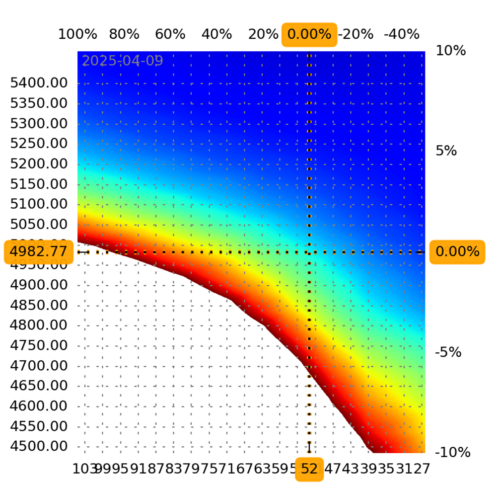

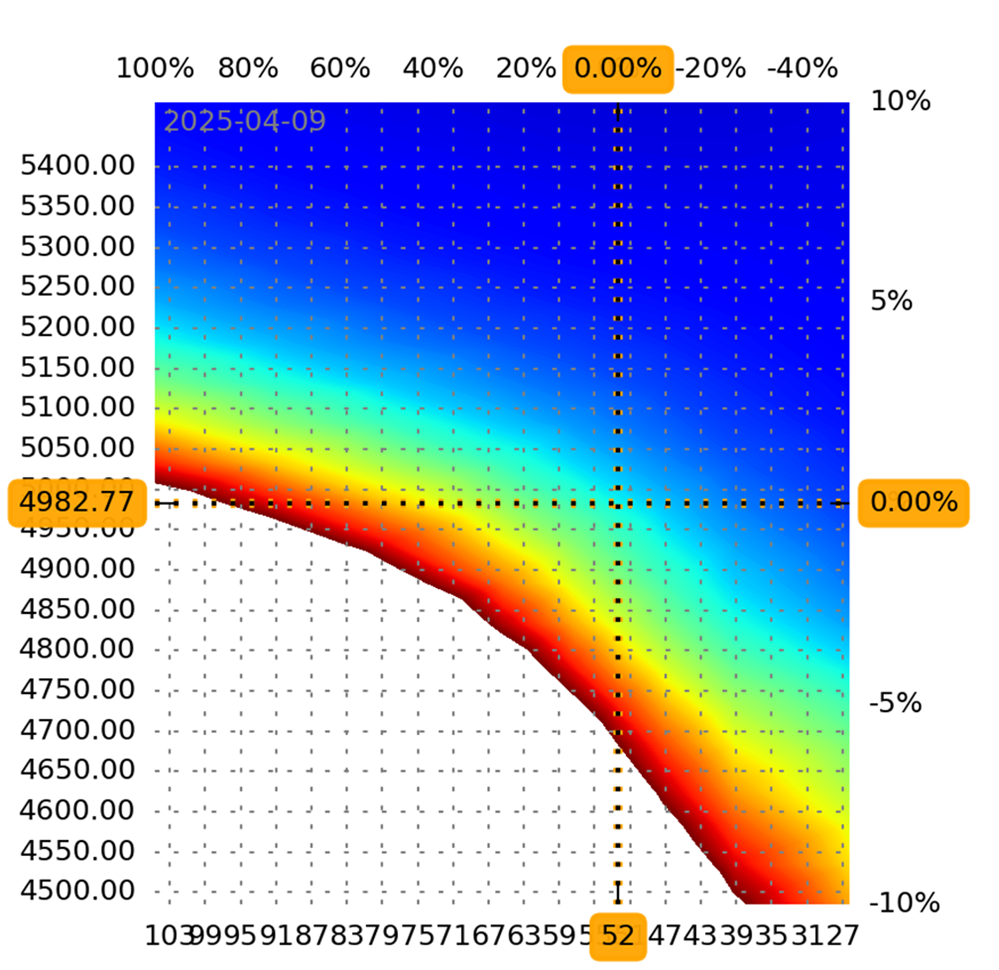

The expectation of a perma-Fed Put stopped people from buying actual SPX Puts. This has created a pool of illiquidity underneath the S&P500, illustrated here by SqueezeMetrics who monitors gamma from option flows – the left hand axis is the SPX level and the axis along the bottom is the VIX:

Suffice to say that when you go beyond red and the chart disappears, liquidity disappears.

This is akin to Silicon Valley Bank or LDI funds failing to buy insurance to cover higher interest rates – in fact they both added to exposure that anticipated interest rates would fall, thus sowing the seeds of their own destruction. Higher inflation was always going to bring higher interest rates but cognitive dissonance prevented them from acting accordingly.

Now we are getting the same reaction in the much bigger market of the S&P500. And with that comes contagion to other assets, hence selling off supposedly safe US treasuries, getting out of credit and exiting positions that had made money such as being long of Gold.

This is starting to get out of hand and look rather systemic, leading to questions of whether Trump will change course and whether the Fed should/could/would step in.

3. When 1 meets 2….

The Trump team had a plan but that doesn’t mean it can’t shift. In part the element of shock is grist to the Trumpian mill. Keep your head whilst all around you are losing theirs and Trump thinks he will be the man. He was always prepared to take more pain than the rest and he thinks China is on the ropes thanks to the bust in its real estate, slowing inflation and meagre growth.

Trump is still a pragmatist. This was always really about China. But it had to be about everyone else too. Bessent pointed out in his article ‘bilateral actions largely shift imbalances around rather than address their underlying source’. If everyone else plays ball, Trump can welcome them into the fold, isolating China. For all the arguments over how the reciprocal tariffs were calculated, Trump explained them as follows in his Rose Garden address: “That means they do it to us and we do it to them. Can’t get any simpler than that“.

For financial markets, we are reaping the consequences of the extreme interventions of five years ago. The Fed and other central banks were supposed to keep markets open, not up. When they come to resolve a market dysfunction this time around, that fact will come as a nasty shock. Volatility is back and here to stay, whether Trump achieves his new world order or not.