The Two Weeks That Will Be (11 May 2025)

All the data in the world doesn’t matter when Politics is in the driving seat. For all the inevitable focus on the latest US inflation print due on Tuesday it is still firmly in the rear view mirror. Tariff rates are yet to find their final resting point and companies are yet to determine how much of the cost to pass on to consumers, whilst consumers are yet to decide how confident they feel about buying dolls for their daughters for Christmas (the litmus test according to FOX News in recent questions to Trump and Bessent).

This left Powell waiting at the latest FOMC meeting – according to the WSJ’s Nick Timiraos he used some version of the word “wait” 22 times at the press conference. He has the benefit of the doubt for now but no action is still a policy choice. Powell is hiding behind the useful veil of economic theory to avoid a political conflict. President Trump wasted no time in repeating his accusation that Powell was “Too Late”, telling reporters ‘the Bank of England cut, China cut, everybody’s cutting but him‘. Powell admitted at one point in the press conference ‘I wouldn’t say that what we did last fall was at all preemptive. If anything, it was a little late‘. Perhaps he was wistful that if the Fed’s December 2023 pivot had not waited until a September 2024 rate cut, he could have been facing a different character in the White House. The US data will tell us very little when Powell deliberately wants to be reactive rather than pro-active.

Even pro-active central bankers are split, as the latest Bank of England decision demonstrated. We will hear from seven of nine MPC members over the course of the next two weeks. Four of them, along with two former members, Lord Mervyn King and Sir Paul Tucker, will be speaking at the annual Bank of England Watchers Conference on Monday. We will have one from each side of the decision: Lombardelli and Greene were in the majority voting for a 25bp cut, Mann reverted to her hawkish roots with an unchanged vote and newest MPC member Taylor wanted a full fat 50bp cut.

Upcoming data is unlikely to provide any clarity: Q1 GDP on Thursday is largely known and discounted as bringing forward of pre-tariff/pre-tax hike activity; Inflation on Wednesday 21 May is prey to the same irrelevance as the US print; and the less said about the ongoing shambles of the jobs report on Tuesday, the better. The BOE have even had to come up with their own measure of the labour market in the latest Monetary Policy Report – and it suggests employment growth is softening:

Can we forgive central bankers their uncertainty? The BOE referred to the spike in yet another uncertainty index:

How can tariffs from a leader who has previously used tariffs and has talked about using them for forty years create quite so much uncertainty – even more than in the turbulent 70s and 80s. The answer lies in the footnote to this chart:

‘The trade policy uncertainty index reflects automated text search results of the electronic archives of seven newspapers discussing trade policy uncertainty: Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, Guardian, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post.’

There are many reasons why these particular publications want to shout about trade policy – some of it political, some of it clickbait, some of it groupthink – but it is at least as much a reflection of the changing nature of the media as it is a genuine matter of concern. The BOE have constructed their own UK uncertainty index which looks to offer a more balanced approach:

This index is constructed from a mixture of market volatility, survey data and forecasts for GDP and earnings. (If you want the full list: ‘three-month option-implied FTSE volatility, three-month option-implied sterling exchange rate volatility, dispersion of consensus GDP forecasts, GfK expectations of the general economic and financial situation over the next 12 months, PMI services expectations one year ahead, CBI demand uncertainty limiting investment, standard deviation of analysts’ forecasts of 12 month ahead company earnings growth for the FTSE All-Share index, the UK economic policy uncertainty index, and a trade policy uncertainty index.’)

It suggests uncertainty is approaching some of the high points of the second phase of the pandemic but short of when Covid first appeared, or when the financial crisis took hold.

And yet a hair-raising spike in uncertainty fits the narrative when the S&P500 suffered such a huge impact in the wake of the tariff announcement. This is less to do with the actual uncertainty and more to do with the huge policy interventions of the past twenty years. They have created a Pavlovian reflex that any shock would be met by a soothing wave of rising liquidity. Uncertainty might not be high in absolute terms but the shocking reality that a policymaker – perhaps the most powerful policymaker in the world – might do something to force a revaluation of risky assets has caused consternation akin to grief.

Here is a chart of the long-running American Association of Individual Investors survey which shows the longest streak of negative sentiment in its history:

Retail investors have been buyers of US stocks for the last few weeks so this survey might contain some selection bias. But it’s the relative balance that seems out of line. Do respondents to this survey really feel more bearish now than when an investment bank failed, the stock market plunged after Congress voted down TARP, and countries started to go bust? Or after the arrival of a virus that closed down the world economy and forced people to stay at home?

Rather we should consider such negativity indicates a lack of resilience after a series of shocks and the inability to throw away the old rulebook. As Gillian Tett put it in the FT, “Welcome to the new era of geo-economics“, where ‘Tech, trade, finance and military policies are mingling in a manner not seen during the neoliberal era’. The truth is that this never went away but the persistent use of QE rendered it of less interest to financial market participants. Constant liquidity and the rise of computer power created an arms race for quantitative capability, crowding out qualitative matters such as Pakistan attacking India (airstrikes took place in 2019) or Russia shooting down a Malaysia Airlines flight over Ukraine (in 2014).

It took the return of normal interest rates to re-establish normal political economics. The current environment might feel difficult but it is known unknowns. Determining the final set of tariffs should be similar to forecasting the peak or trough of interest rates. Remember August 2007 when the word recession featured nowhere in the BOE Inflation Report? What about how the BOE subsequently looked through high inflation of 5% in September 2008? Central bankers have always had to make the argument, just as politicians do.

Trump has been remarkably consistent in making his argument for tariffs. They will not be going away any time soon. We can be sure the overall tariff rate from America will be materially higher than it was before. We know his position and his relative strength, having just won a majority and a mandate. The UK fell into line, understanding that agreeing to something was better than the alternative. China, the real enemy in Trump’s sights, will prove a more formidable negotiator. But negotiations always follow the same path – thrashing around, threats and then someone concedes something. It takes time and each side’s position can change based on their relative strength. Congress remains in thrall to Trump but it is unlikely to be subdued forever. China face no such democratic constraints but they do still need to avoid a restive population. Companies will decide which supply chain they want to be part of – the Americans’ or the Chinese. Earnings will struggle in the short term. Some will be better placed than others through the bifurcation of world order. Walmart reports on Thursday. Trump will now focus on tax cuts to provide a boost to consumers.

Just as investors thought they had only to parse an FOMC statement for signals, now they must assess how far Trump and Xi are willing to go. Trade and Defence are two sides of the same coin. In the economic war, who do you think will win? What tools will they employ to gain an advantage? Financial markets have become a weapon. Investors are in the game whether they like it or not.

Is it really a credible threat for Japan to claim it might use its pile of US Treasuries to extract a deal? On 2nd May the Finance Minister claimed they were a “card” on the table; three days later he clarified “We are not considering the sale of US Treasuries as a means of Japan-US negotiations”. Japan and its pacifist constitution means that they rely on the US for its military might. You and whose army has become the Trumpian cri de coeur in trade negotiations. International law is only a matter of whether the USS Gerald Ford is parked alongside your coast.

Recent electoral results suggest voters have got the message. They have chosen to give as much strength as possible to the victor. Canada, where minority governments often prevail, saw the Liberal Party come tantalisingly close to winning an outright majority (currently 3 seats short as recounts are still taking place). Australia, also plagued by unstable governments, saw Labor take its largest number of seats in a landslide victory. Even the one-party state of Singapore saw a rebound from the previous poor result for the People’s Action Party, taking 66% of the vote from 61% in the Covid ravaged 2020 election.

In Canada and Australia the drive to consolidate the vote saw the big opposition party leaders lose their seats – and not just the right-wing Poilievre in Canada and Dutton in Australia, but also the centre-left Jagmeet Singh of the NDP, enough of whose voters decided to boost the Liberals instead. The Canadian Conservatives even saw their highest share of the vote since 1988 despite Poilievre’s defenestration (could the metre-long ballot paper have played its part?!) as voters coalesced around the two main parties.

All of this comes at a cost, as Germany has shown. Papering over the cracks of a splintered electorate becomes stretched to breaking point. Friedrich Merz pushed himself into yet another grand coalition and dropped his party’s commitment to fiscal rectitude within days of the election. As a result, he became the first Chancellor in post-war German history to fail to be elected by the Bundestag in its initial vote. In the secret ballot it appears some of his own party’s MPs chose not to back him, or at least were inexplicably absent. A few hours later this apparent oversight was corrected and Merz won the second round vote. He has however been fatally wounded. The coalition will not last. It has barely begun! It is already having to bend to AfD policies, with the new Interior Minister immediately announcing tighter border controls which will “lead to a higher number of rejections“. Poland isn’t happy, with Tusk saying in a joint press conference with Merz that “There is an impression at the moment that Germany is sending groups of migrants to Poland and we cannot accept that”. All of this should challenge the view of those who prefer Euros to Dollars on the grounds of lower political risk.

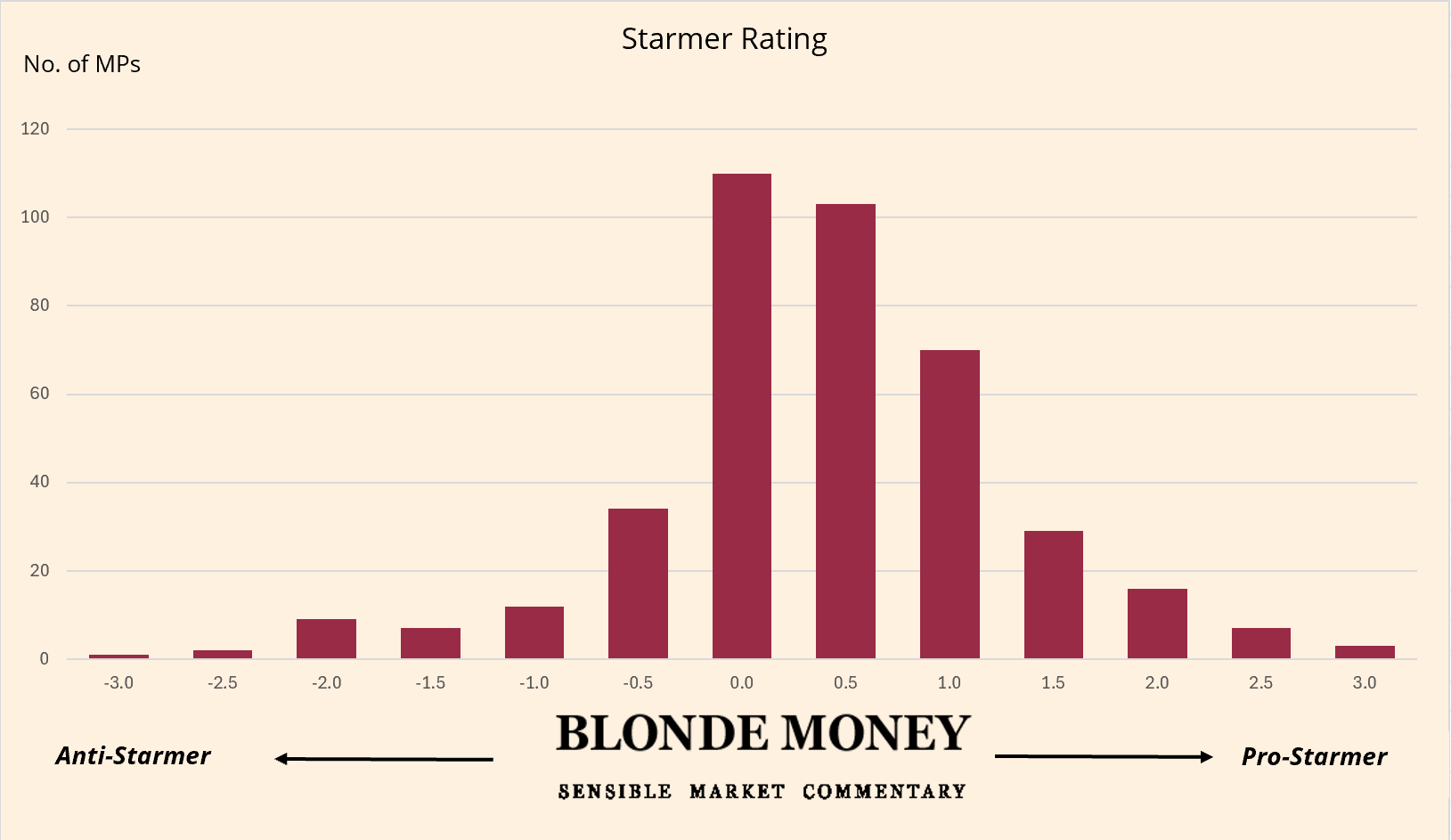

In the UK, Starmer faces the same inexorably centrifugal force of discontented voters. He has become bound by the logic of his Truss-distressed Chancellor. He cannot square the circle of pleasing his core voters whilst butting up against the constraints of Reeves’ fiscal rules. It’s all very well for 80 MPs to issue a statement and 42 MPs to write a letter in protest at the removal of benefits but they should be mindful of what the market can do if the government appears unable to stick to its plan. There are Gilt Auctions on Wednesday and Wednesday 21 May. The market can impose discipline but at the price of Reform at the top of the opinion polls. We are now heading into a tightening noose around the PM. Yields rise or growth falls –> tough decisions –> polls drop –> party fragments –> can’t meet own rules –> yields rise… and so on.

It’s a bumpy ride but it is not an uncertain one. It just requires a new framework. This is why we have rebooted our podcast. You can listen here orsubscribe on Spotify, Apple etc to hear from Ben Ashby, CIO of Henderson Rowe, in discussion with our CEO Helen Thomas as they discuss where systemic risk lurks and what role the Eurodollars market has to play. Your feedback is welcome!