The Countdown Budget – Part 2

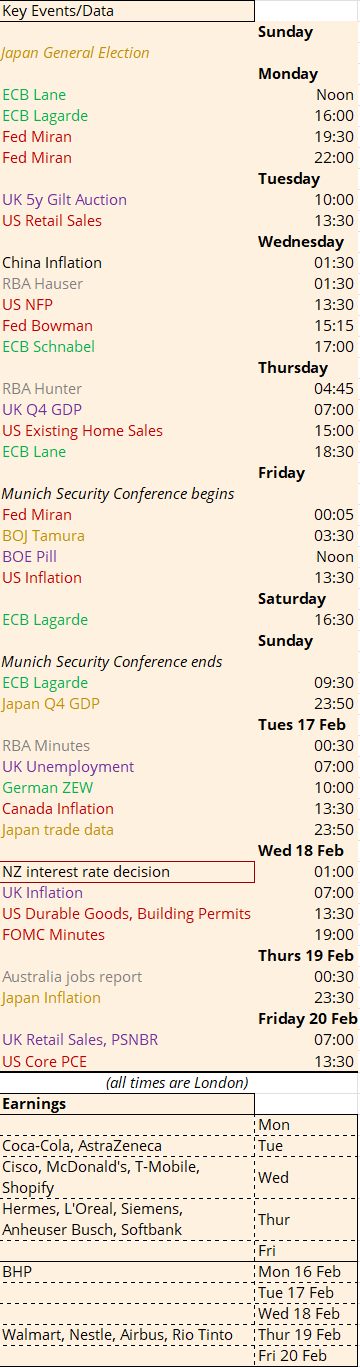

- To summarise, the Budget sets out:

- ~£70bn of extra spending each year for five years

- Two thirds on current and one third on capital spending

- Half of this to be paid for by tax rises and half by borrowing

- ~£70bn of extra spending each year for five years

- The borrowing is ~1% of GDP per year so that’s 5% of GDP in total over five years, ‘one of the largest fiscal loosenings of any fiscal event in recent decades’ as the OBR puts it.

- The vast majority of increased tax revenues (£26bn of £36bn) comes from the increase in employer NICs.

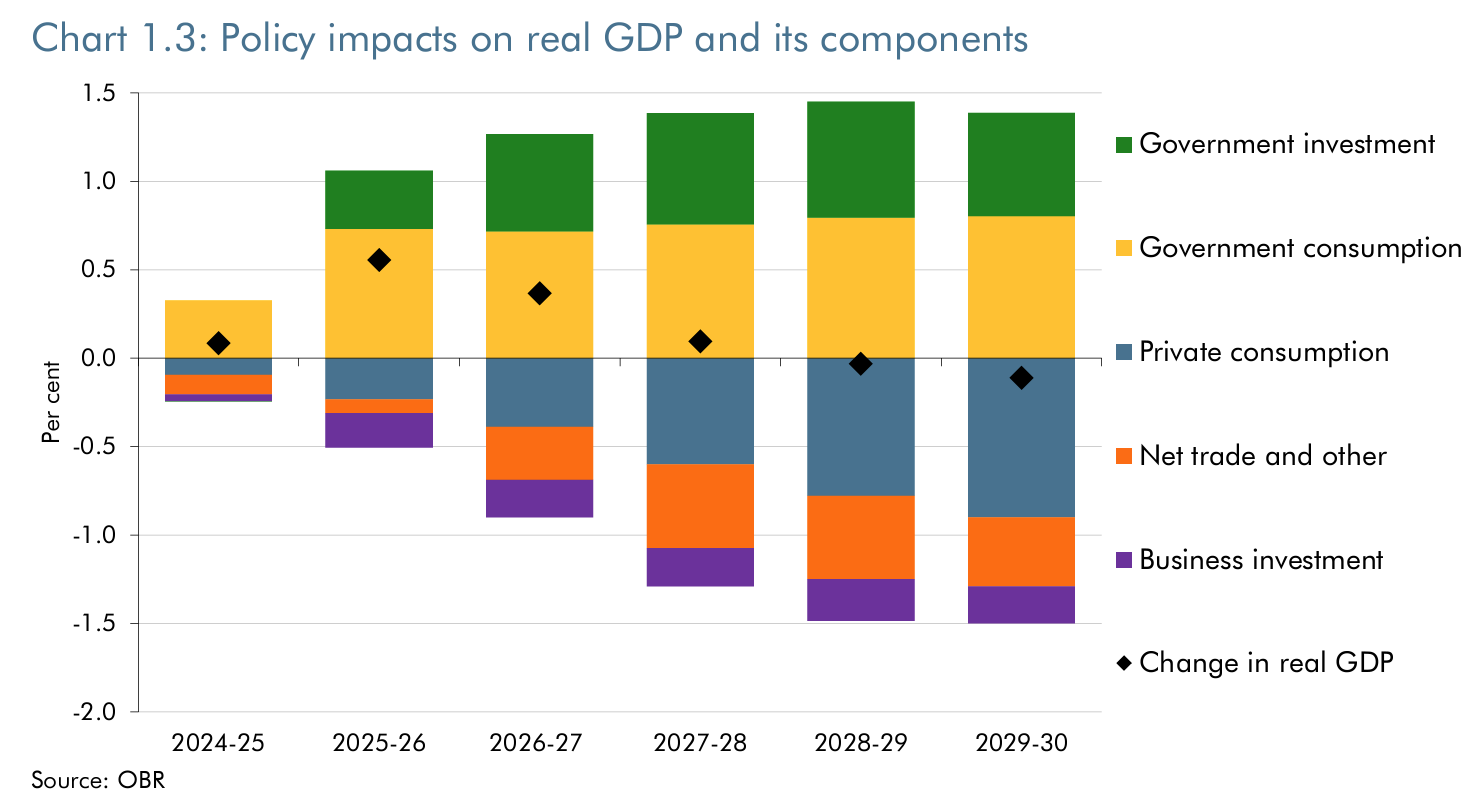

- The net effect of all of this on growth is… not very much. There’s a short term boost which fades. The government crowds out the private sector.

- The OBR anticipate this raises inflation in the short term which, all else equal, led them to add an extra 25bp onto their Bank Rate and gilt yield forecasts.

- And with more borrowing, comes more exposure to interest rates. The OBR note: ‘Market expectations for Bank Rate and gilt yields remain volatile. If these were 1.3 percentage points higher across the forecast, it would be enough to wipe out the headroom to the supplementary fiscal target‘.

- And the amount spent on servicing debt is increasing anyway as a result of the higher borrowing: ‘The increased borrowing to finance the policy package results in a higher central government net cash requirement of £22.9 billion a year on average compared to March. This adds increasing amounts to debt interest spending, reaching £4.7 billion in 2028-29′.

- The borrowing is front loaded:

- But the government want you to think about the long term, where investment begets investment:

- The new adjusted fiscal targets are met (obviously) but with about the same headroom as Jeremy Hunt had in March:

- Reeves has managed to get the budget deficit into surplus in three years:

- But the whole edifice is prey to only small shifts in interest rates, inflation and growth:

- As we thought in our preview to The Countdown Budget, the Chancellor chose levers that would be certain to produce a big chunk of money mechanically rather than getting bogged down in those prey to behavioural assumptions.

- Changes to capital gains tax were therefore minimal, with the carried interest on private equity only assumed to raise £100million:

- ‘Overall, the costing assumes that around 12 per cent of carried interest earners, who account for a quarter of all carried interest gains, are at high risk of migrating within the forecast period and taking a portion of all their receipts with them. The reduction in declared gains and other tax receipts from this group reduces the yield to £0.1 billion in 2029-30. This modelling is highly uncertain as it is driven by the behaviour of a small number of high-net-worth taxpayers’.

- Inheritance tax changes are expected add up to £2.3bn over five years but the OBR warned ‘The costings of these measures are unlikely to reach a steady state for at least 20 years‘.

- And for VAT on private schools they almost give up entirely: ‘The costing of this measure does not directly include any additional government spending for the cost of educating pupils who move to the state sector. Such costs would be included in spending allocations made by the government at spending reviews. However, the cost of 35,000 additional state sector pupils would be around £0.3 billion, based on a £7,690 per pupil cost in England’.

- The non-dom changes are thought to raise an average of £4bn in the first couple of years but only £0.1bn by the fifth year.

- This really was 3 from the top and 2 from anywhere else.

- All of which suggests that she left these measures in to fulfil manifesto promises without frightening very wealthy horses – although the rise in second home stamp duty surcharge and other measures suggests the slightly wealthy are still within her sights.

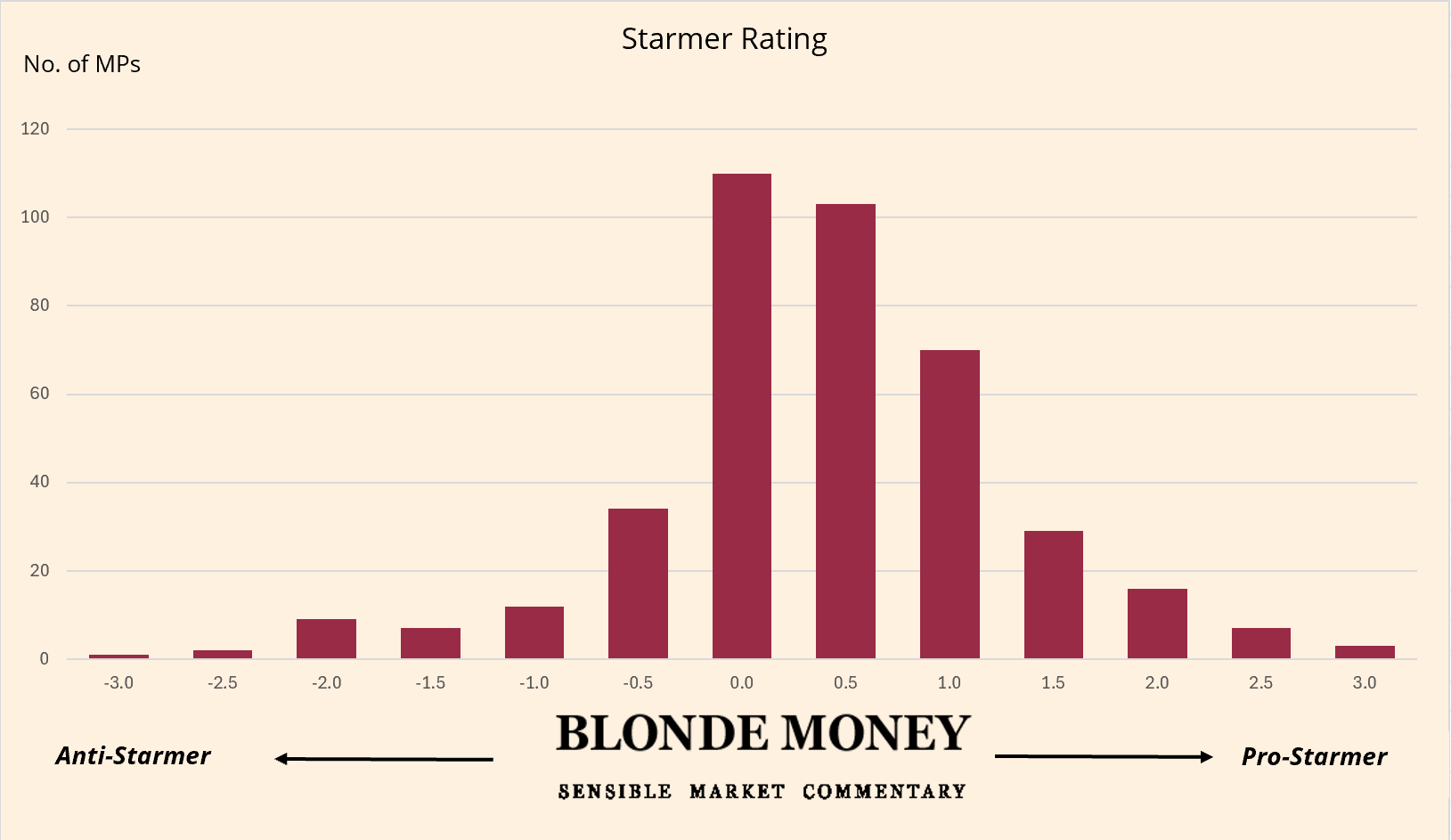

Overall this is a Budget in line with the principles Rachel Reeves set out in her Mais Lecture. Go hard and early on public sector investment, borrow and tax to pay for it and then reap the growth rewards down the track. The relatively easier ride given to private equity shows that lobby groups can still exercise power over a Socialist-inclined government but the fact she then had to go for a big tax like NICs shows she had a harder time than she had expected to find the money to fill the gap. This was as close to a breaking a manifesto promise as she could get – a remarkably binding constraint despite the scale of the election victory. And her own party will be agitating for all that borrowing to be invested in their pet projects.

Rachel Reeves did her homework. The sums add up and she took a handful of tough, albeit blunt, decisions. She has so far managed to answer the question “How do I avoid the market sacking me?” without really answering “How do I credibly grow the productive capacity of the economy with so much debt?”.

The spreadsheet swot is taking a gamble. She has gone all in on her ideology that an actively investing government will deliver growth, even as she imposes a tax on jobs. Higher borrowing leaves the government even more exposed to shocks and in particular the threat of higher interest rates. With a deficit-busting tariff-loving President just around the corner in the US, she had better hope growth hoves into view pronto to convince the markets that she can pay off the debt she is about to rapidly incur.