The Two Weeks That Will Be

1. The US

As we head into the final straight before election day on Tuesday, one of the factors that had been to Trump’s advantage is starting to slip away: that of momentum, reflected in a slight narrowing of the polls. This has showed up most startlingly in the final Ann Selzer poll for Iowa where Trump’s lead of of 4 pct pts in September has flipped to a 4 pct pt Harris lead. Given Iowa had a low winnability ranking for Harris, and Selzer has a decades long track record of accuracy, this has set the feline amongst the columbidae.

It doesn’t however change the outcome. Harris still has a mountain to climb given the stacking of electoral college votes requires her to take all three rust belt states and the circumstances of her accession. The excitement generated by one poll of 808 people with a 3.4pct pt margin of error rather illustrates the point that, of the two camps, it’s the Harris campaign holding out for a Hail Mary.

The Senate looks set to flip into Republican hands with the Democrats having to defend four of the six narrowest races and Montana and West Virginia almost certainly lost, putting a ceiling on the Democrats at 49. If the Republicans retain the House and it’s a red clean sweep, the GOP might just be less fractious, at least at the start of the term.

All of which means, get ready for DJT v2.0. Tariffs, tax cuts, tougher immigration policies, bigger deficits and more debt.

When the Fed meet on Thursday they will be loathe to do anything. Unfortunately the market is pricing in a 25bp cut along with another for the following meeting in December, a nice 50bp of easing just ahead of a reflationary inauguration in January. Powell will therefore need to buy some optionality in his press conference, perhaps signalling the terminal rate might be higher than they thought, so there will be fewer cuts to come.

The Fed will still cut by 25bp this time round but the market is ahead of them anyway, pricing higher interest rates ahead. As this chart from Bianco Research shows, the rise in 10 year yields after the first rate cut has never been so large as it has this time round:

That’s because it isn’t really a cycle. We have been far from a true business cycle since the pandemic soundly kicked the economic jigsaw puzzle into the air and all the pieces are only still falling back into place. The election will provide another jolt. The US has managed to bear down on inflationary pressures even as growth has returned, thanks broadly to an influx of immigrants. That is now set to change significantly. Whether you think Trump will be stagflationary or reflationary, the long end of the US yield curve risks becoming untethered.

2. The UK

This might be manageable if you are in possession of the world’s reserve currency but it’s rather more problematic for everyone else, as Rachel Reeves found out after unveiling her first Budget. The Gilt market suffered a serious bout of indigestion when presented with the OBR’s analysis of significantly more debt for not very much growth. Taxing businesses to provide breakfast clubs for schools did not convince the market to give Reeves the benefit of the doubt.

The move in Gilt yields, whilst by no means of the scale or speed of what took place under Truss, was nevertheless significant. It was the largest increase in 10 year yields over two days for any Budget since 2006 – aside from the 2022 episode. See this chart from Deutsche:

Absent the impact of negative convexity in LDI strategies in 2022, the market reaction to the latest budget would have warranted significant concern. Ed Conway at Sky showed the move in the 5 year yield in two days had already eaten into half of the headroom in the OBR’s projections:

And these are just projections, based on data that has already moved on. The economy doesn’t stand still at the moment the OBR sets its forecasts. Some of the overspend that formed part of the so-called ‘black hole’ came about precisely because life doesn’t pan out as the Treasury expected. Higher inflation led to higher costs, particularly in terms of pay. If a Trump victory sets off higher market interest rates and higher inflation through higher tariffs, there will be more unexpected overspends.

The problem is that the government is operating right at the event horizon of what is possible with so much debt. Rather than a £22bn black hole there is the white giant of £400bn of debt incurred during the pandemic. For some reason neither party saw fit to discuss this galactic question in the election campaign.

This has left the new government in just as much of a pickle as that faced by Truss – neither had a mandate for the revolution required. Liz Truss acted as if she had been elected by the country rather than 150,000 Tory members whilst Starmer/Reeves got a large majority by promising no rises to the four main taxes. Contrast with 2010 when the Conservative Party entered government, albeit a coalition one, having run an entire campaign promising austerity to get the books back into balance. Once elected on such a platform, the programme can be implemented. Without a mandate, credibility is stretched.

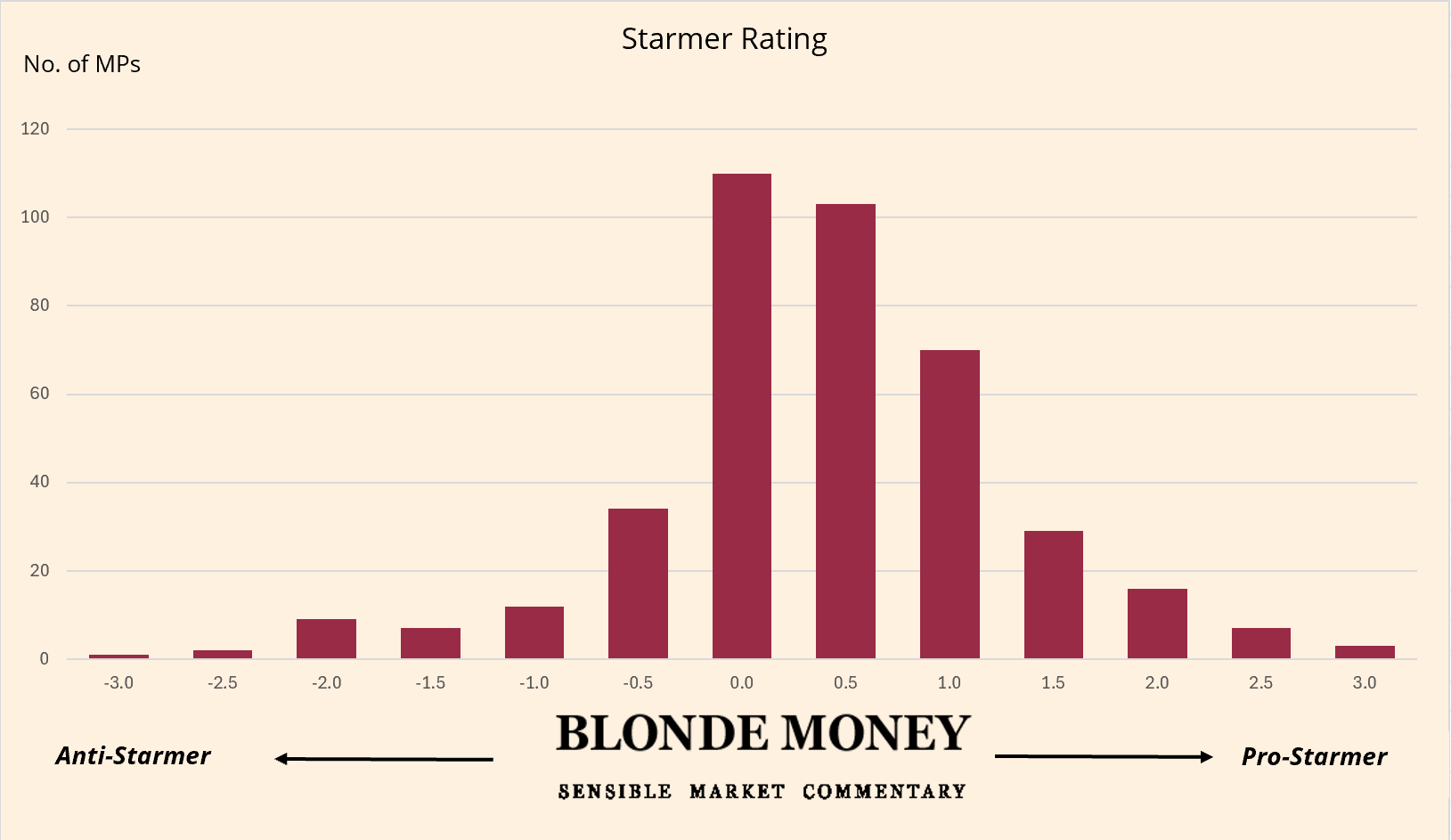

Not that the Labour Party need worry, such is the scale of their majority. The Conservatives and Reform can whiz up the polls but it need not bother Sir Keir, unless – or rather until – his own party become restive. Any further increase in market interest rates would provide kindling to such a fire. Starmer is evidently concerned about the market reaction because he wrote a letter to the FT in an attempt to sell the Budget. He emphasised ‘the enormous value of certainty‘ to business. He said it’s not all about growth but reform: ‘Just as we cannot tax and spend our way to prosperity, nor can we simply spend our way to better public services‘. This was a decent sales pitch, although markets react to the information they have, not what politicians merely promise. And Starmer goes on to admit that he doesn’t have the information yet: ‘This process involves detailed, often painstaking work. For that reason, it is not yet ready to be included in the OBR’s forecast for growth‘.

Markets don’t wait. Starmer/Reeves got their first chance to establish their credibility and the market duly put them on notice. There is now a risk premium in Gilts that will be tough to eradicate. Reeves’ initial response in an interview to Bloomberg during the Gilt/GBP sell-off demonstrated she has yet to grasp this reality. When asked if she was worried about the moves, she replied that ‘the number one commitment of this government is economic and fiscal stability which is why we put in place robust fiscal rules that we will meet two years early‘. A commitment to stability is laudable but irrelevant if your plans have created market instability, whilst saying you “will meet” rules two years early doesn’t make sense if the market moves are reducing the likelihood you’ll meet them at all.

It feels as though she was caught on the hop. Treasury Minister Darren Jones at least proffered a simpler response when he said in the aftermath, ‘it’s normal for markets to respond’. He’s right – the reaction was a rational re-pricing.

He concluded, perhaps more honestly than he intended, ‘we’ve all got Liz Truss PTSD’. The Truss episode has guided Reeves more than anything. Kwarteng fired whilst at the IMF meetings? Reeves made sure she got their stamp of approval whilst in Washington. Planning reform, more power for the OBR, crowding in of investment for net zero? All recommended by the IMF, as former Treasury Select Committee chair Harriett Baldwin pointed out in June. Even the public sector pay rises had to happen straight out of the traps so that strike action wouldn’t weigh on OBR growth forecasts.

Rachel Reeves is fast discovering that not being Liz Truss is only a necessary but not sufficient condition for remaining in post. Making the numbers add up for the OBR doesn’t mean markets won’t move and doesn’t mean the economy will pan out as planned. Rather than worry about Truss, the real question is the self-confessed girlie swot must answer is “How will you credibly grow the productive capacity of the economy with so much debt?”. Moody’s marked her homework in the could-do-better camp when they concluded that ‘the increase in borrowing, which is in part supported by a new measure of debt under the fiscal framework, will pose an additional challenge for what are already difficult fiscal consolidation prospects’. Reeves claimed in her Budget speech, that ‘a strong economy depends on strong public finances’ but if she can’t deliver on the latter then she will struggle to deliver on the former.

The Budget has also created a challenge for the Bank of England who meet on Thursday. They will still deliver a 25bp cut but their quarterly monetary policy report will have to deal with a different path ahead. The OBR believe that the package of measures will raise inflation and this will lead to fewer interest rate cuts from the Bank of England – see the difference between the dotted ‘pre-measures’ forecast line and the solid blue line:

The OBR explains that it is raising its inflation forecast because of higher wage persistence, excess demand generated by the fiscal loosening, and pass through of the rise in employer NICs. If the BOE don’t agree, it will be interesting to see why.

3. The ECB

For once the ECB has the easier roadmap ahead. The sheer lack of growth in the Eurozone has created an immaculate disinflation into which the doves have gained an iron grip. Lagarde speaks Tuesday and Schnabel and Lane on Thursday. Chief Economist Lane will be at a very timely conference on “Public Debt: Past Lessons, Future Challenges” hosted by the Central Bank of Greece, who have rather a long history on such a topic.

It is no longer the periphery of the Eurozone who have debt problems but rather the core. The governments of France and Germany would give anything to have Rachel Reeves’ majority and must be perturbed to see the market sell off with a budget they would rather like to give. Mario Draghi reflected this with his piece in the FT entitled ‘Europe can learn fiscal lessons from the UK on how to achieve its goals’.

4. Germany

Germany has to agree its budget by Friday 15th November and all the signs are that it will become a set-piece moment for the three party coalition to collapse. Economic Affairs Minister Robert Habeck of the Greens has come up with a 14 page position paper which included a multi-billion ‘Germany Fund’ for investment which would circumvent debt rules; Finance Minister Christian Lindner of the FDP has responded by circulating his own 18 page document which calls for tax cuts and a halt on all new regulation. Chancellor Scholz has now called them both into meetings to seek common ground. Scholz can hardly pretend to be the conciliator, given he created a business investment summit to which he invited neither of the other two men.

While none of the parties would relish an election given they’re all floundering in the polls, it is becoming apparent that remaining in the coalition will yield worse results than breaking free. This is particularly the case for the FDP who are facing an extinction-level event as they’re polling below the 5% threshold that the German electoral system requires to gain any representation. A majority of the public now wants the coalition put out of its misery with 54% supporting a snap election in the latest poll from ARD. Lindner has form on dramatic departures – in 2017 he walked out on coalition negotiations after four weeks of talks with Angela Merkel’s CDU. It was more surprising that he actually joined up with the SPD in the election of 2021 – we argued then that doing so would be the end of Lindner or the end of the FDP. He has two weeks left to save himself and his party. We believe that to stand a chance of doing so, he must leave the coalition – or, more likely, be pushed out.

The Greens and the SPD could try to continue as a minority government but this is rarely tolerated in Germany for long. Better to go out in a blaze of glory after a Budget vote, fighting for what your core voters believe in, and then kick off a proper election campaign. Early elections are coming.

5. Liquidity

Into all of this political upheaval we are entering the twilight of the year where liquidity would usually start to diminish. S&P500 gamma has dropped although not quite into negative territory. We still have a number of big earnings reports to come including Arm and Qualcomm on Wednesday and Tencent and Cisco on Wednesday 13th November.

The latest results from Berkshire Hathaway show that Warren Buffett has moved even further into cash, $325bn of it, which would rank as the 28th largest company in the world. This doesn’t exactly smack of confidence in the markets at current valuations. We have a big two weeks ahead.