UK: Anatomy of a Rolling Fiscal Crisis

Summary

- The Labour landslide honeymoon has given way to discontent and in-fighting

- The Gilt market will force the government’s hand, prompting an irreconcilable ideological split

- The Bank of England can smooth but not solve the ensuing rolling fiscal crisis

The Challenge

The large Labour majority hides a serious problem for the Gilt market: the government has no mandate to deliver a credible plan. Simply being a change from the Conservatives whilst taxing jobs, farmers and family businesses and removing benefits from the old and the disabled does not a policy platform make. Even if it did, it’s one that many Labour voters, not to mention Labour MPs, did not back the party to deliver. Hence the precipitous decline in the polls and astonishing level of rebellion from a party that only one year ago won an historic landslide.

The tears from the Chancellor on 2nd July signalled the beginning of the end. She had tried to square the circle of pleasing markets and pleasing her party, only to find saving £5bn for a country spending £100bn on debt interest alone was a step too far. The debt sustainability circle cannot be squared by a tax-and-spend Labour government. The market will bring matters to a head, forcing an irrevocable split within the Labour Party that ushers in a rolling fiscal crisis which can only be resolved by a general election.

The Political Constraint

There were enough potential rebels over welfare reforms that the government had to gut its own bill on the floor of Parliament just moments before the vote was due to take place. Even with the substantive changes removed, 49 Labour MPs still voted against their own government. Four of the rebels subsequently had the whip removed as punishment, taking the government’s working majority down to 155. This number looks impenetrably solid as it would require 78 MPs to rebel in order to defeat government legislation. But a closer look at the position of Labour MPs shows that it is dangerously fragile.

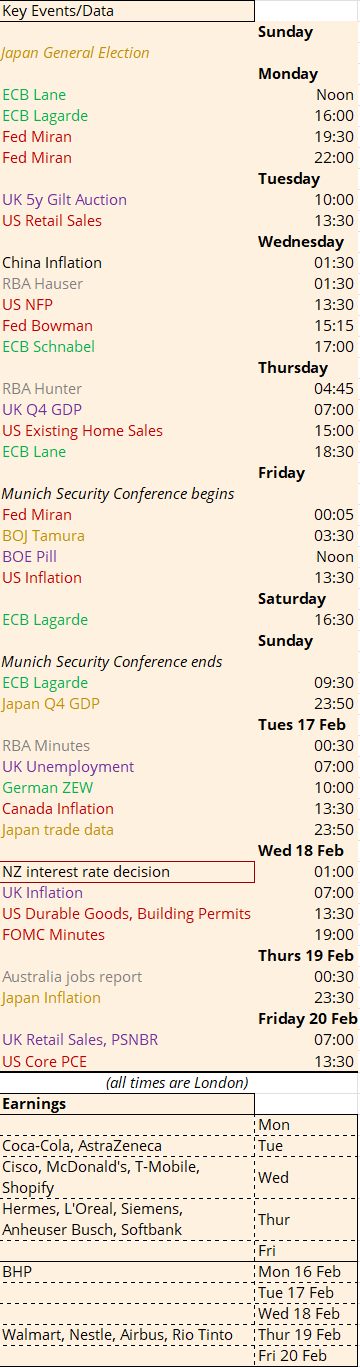

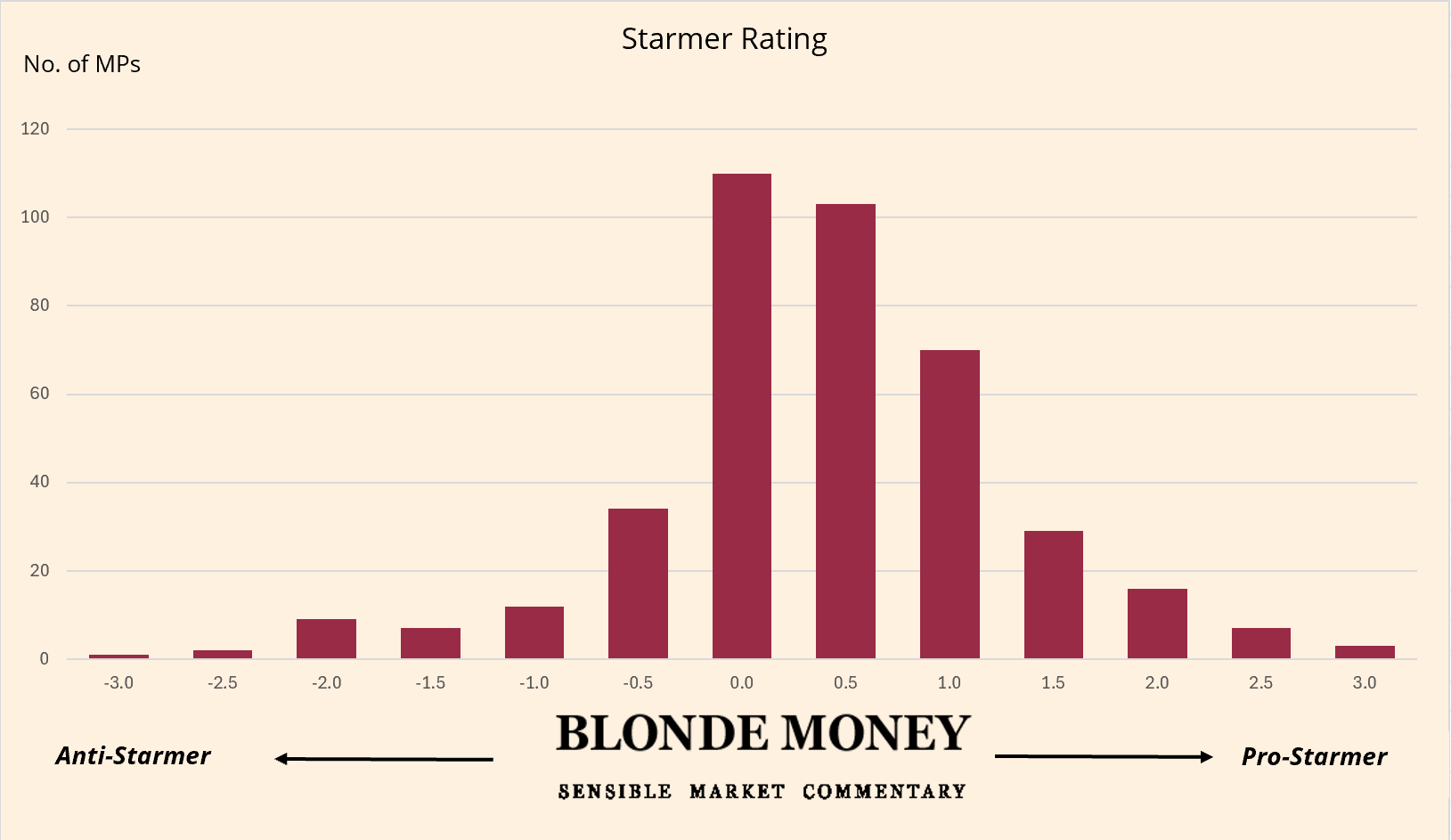

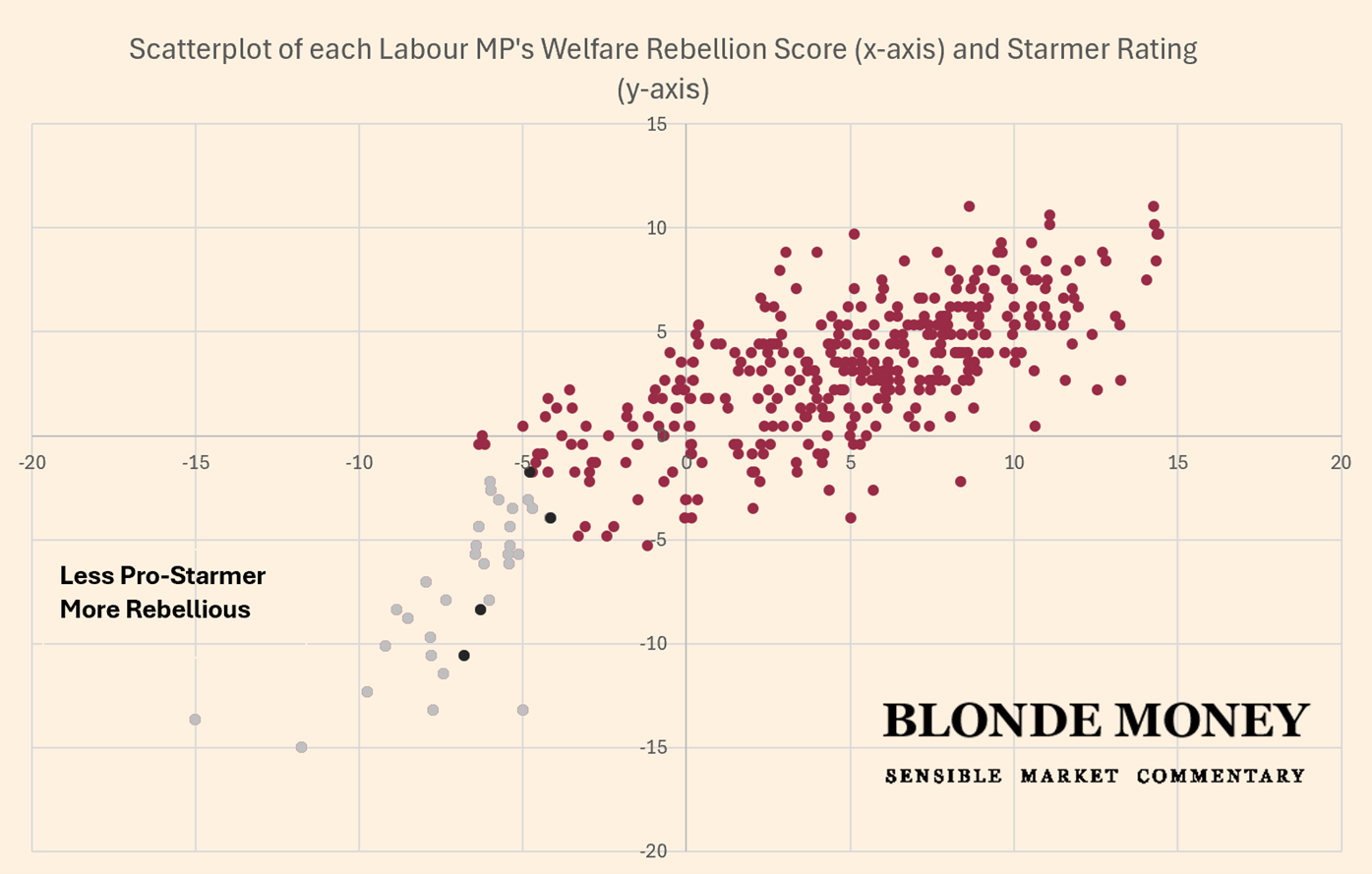

We created a “Starmer Rating” and “Welfare Rebellion Rating” for every Labour MP based on various quantitative criteria, including the MP’s majority, voting record and constituency profile. Plotting one against the other creates quadrants of loyalty, with the bottom left of the graph showing MPs who are less pro-Starmer and more likely to rebel. The four MPs who lost the whip sit in this segment, shown as black dots:

The total number of MPs in this quadrant of the graph is 66, just 12 short of the point at which a majority would be lost. Similar analysis that we have conducted on MPs of all parties over the past eight years has shown that those in the middle of the distribution tend to side with the more extreme elements once the leadership loses control. Momentum is everything in politics.

And momentum is with the rebels. They managed to force the government to delay welfare reforms, hot on the heels of the Prime Minister announcing a u-turn on the unpopular removal of the winter fuel allowance from pensioners. The rebels have realised they have veto power. So far only four of their number have lost the whip for intransigence. As the rugby player Willie John McBride once put it during a combative match with South Africa, “they can’t send us all off”. The relatively benign response of Gilt markets only emboldens their position, grist to the mill that Rachel Reeves has been crying wolf whilst forcing them to eat thin gruel.

Reeves’ position is untenable. She has been fatally wounded, using up vast amounts of political capital for little return. The woman who declared “I know how to run an economy” in the run up to the election has been exposed. The Truss episode led her to the incorrect conclusion that simply satisfying the OBR would satisfy the markets, whereas it has created a rod for her own back. OBR updates are now targets for the market to aim at.

In her first party conference speech as Chancellor last year she said “We were elected because, for the first time in almost two decades, people looked at us – looked at me – and decided that Labour could be trusted with their money”. By personalising her credentials she has walked into a trap of her own making. Her enemies want her left in place to wear the full consequences of her mistakes.

The Prime Minister knows that it isn’t possible to insulate himself fully from her failure. Hence he has been recruiting his own economic adviser whilst Reeves has lost two of her own. It is said he wants more input over economic decisions, tacitly placing the blame for the failed welfare reforms at the Chancellor’s door.

The Budget Process

This creates significant risk in the weeks ahead. The slavish genuflection at the altar of the OBR has already ensured a drawn out process for compiling the Budget. Whereas before the Chancellor and their team would decide on policies and then present them to the OBR, the process is now reversed. The Chancellor thinks she can only make decisions once the OBR has conducted its forecast modelling and let her know the amount of fiscal headroom. This is what has led to such an interminably long and leaky process. After knowing the number in the OBR’s spreadsheet, the Treasury put together a list of options to plug the gap, which in turn the OBR slots into its own forecasts and hit F9 to update the spreadsheet. If there’s still a gap, the Treasury try again, and so on in an iterative process right up until a few days before Budget day.

The process is not just about fiscal constraints but political ones too. The Treasury regularly come up with policies that might work numerically but could be disastrous politically. The infamous “pasty tax” crept into the so-called ‘Omnishambles’ Budget of March 2012 because of an attempt to remove the loophole on supermarket rotisserie chickens, where freshly baked items avoided VAT if they cooled down naturally. Two months later Chancellor George Osborne had to announce a climbdown as outrage over an increase in the price of pasties fomented. A former adviser to a former Labour Chancellor, Damian McBride, spotted how Osborne had “let these through the net”, warning that his “team were so focused on the big ticket [items]…that they took their eye off the other balls”.

If Number 10 now tries to intervene versus Number 11, more eyes will miss more balls. There will be a private battle played out in public as Starmer and Reeves determine between and against each other which policy sells best. Kites will be flown and shot down and resurrected. Sources have told the Guardian that this will be a deliberate policy; that it will be such a tough budget the government will need to roll the pitch:

‘Advisers believe that a “no surprises” approach will be crucial to prevent negative market reaction. “Last year was a model of how to do it,” one said. “Had we done it otherwise, it would have been a mess.”’

The rise in Gilt yields during the two months ahead of last year’s budget would argue otherwise.

The process itself has become even more drawn out because Reeves entered government promising to give the OBR the full 10 week forecasting period as part of her commitment to ensure the Truss Budget debacle never happened again. Last Autumn she announced the date of 30th October 2024 on 31st July, leaving the OBR to create the timetable below:

Assuming Reeves wants time to prepare the markets – and cling on to the hope that more time allows better data to emerge before the OBR start the forecast process – we believe the budget will take place on Wednesday 26 November, as December would rather undermine the description of it as “Autumn”. The OBR is required to deliver two forecasts each financial year and Reeves said in her March 2024 Mais Lecture that ‘the next Labour government is committed to a single autumn budget every year’. If it is 26th November then the first pre-measures forecast would be 15th October, which would also mark the end of the 12 working day period in which the OBR takes a snapshot of market parameters as input for its model.

As usual, this leaves the Budget prey to market moves such that the calculated fiscal headroom might have disappeared even before the Chancellor stands up at the despatch box. There is a Federal Reserve interest rate decision on 29th October and one from the Bank of England on 6th November. There is an update on the UK’s credit rating due from Moody’s on 21st November. The French and German Budgets must both be presented to their respective parliaments by 1st October. The market’s appetite for digesting government bonds will be sorely tested given global sovereign bond issuance is ratcheting ever higher.

Gilt Markets Teetering

The Gilt market is particularly vulnerable, as both the Office for Budget Responsibility and the Debt Management Office have recognised.

- On 31st July the DMO released its updated guidebook for Gilt-Edged Market Makers (GEMMs). This created a new “Associate” tier of market maker, with both Bank of Montreal and Toronto Dominion falling into this category. In exchange for being “not usually eligible” for Gilt syndications, they would have less onerous obligations on participation in the market. Given BMO only just gained GEMM status in January 2024, it’s hardly a vote of confidence that they have already decided to take a less active role in the Gilt market.

- The DMO has also adjusted its issuance schedule to be more flexible in case of a potential impairment in demand or liquidity: a lower proportion of bonds in the long end and a higher amount as “unallocated”, which allow them to respond dynamically to market conditions. The new Chief Executive of the DMO is keenly aware of the constraints, explaining the lowest proportion of long-end issuance since 1990 by saying “this reflects our analysis of cost and risk for the exchequer, and this also takes into account market feedback on declining structural demand for long-dated gilts”.

- The OBR couldn’t have been clearer in its latest annual Fiscal Risks and Sustainability report, running with the headline of “UK public finances in relatively vulnerable position and facing mounting risks”. The presentation by Chair Richard Hughes concluded:

The headlong rally into risky assets and concomitant drop in volatility has so far insulated markets from wider macro risks. Should the VIX spike above 25, those risks will suddenly be fully priced in.

Complacency

And yet there remains a degree of complacency towards UK government bonds. When the fiscal headroom was lost in the run up to the Spring Statement, it was assumed some spending cuts would fill the gap. The welfare rebellion put paid to that notion. Using the OBR’s own analysis this meant the Chancellor was already in breach of the fiscal rules she has herself continually called “non-negotiable”. If we look at the OBR forecast that accompanied the Spring Statement, the pre-measures forecast showed the first fiscal rule had not been met:

Given the welfare reforms were the bulk of the measures put before the OBR, the failure to deliver them put the Chancellor in breach.

This must have come as a shock to the IMF. In their latest Article IV Consultation they “emphasized the importance of [the government] staying the course and reducing fiscal deficits as planned over the medium term” but it was predicated on “recent reforms to incapacity and disability benefits” which have now been postponed. There was simply no expectation that a government with such a large majority wouldn’t have been able to enact the reforms that it had announced. The welfare reforms were even structured as a Money Bill to expedite their passage, as such a definition means it would become law within one month, with or without the approval of the House of Lords. The IMF and the OBR both simply expected it would be passed without question.

The welfare savings weren’t even a cut to the welfare budget, just an attempt to slow the pace of growth. If the government can’t pass spending cuts, the burden must fall on tax hikes. But it is complacent to assume that enough can be raised from taxes, given the tax burden has already increased to post-war highs.

Despite this, the left of the Labour Party is arguing that wealth taxes are needed. Former Labour leader Neil Kinnock has claimed a 2% tax on wealth above £6m could raise £10bn.

Two Budgets

For all the tax of property taxes, gambling taxes and removal of pension reliefs, the fiscal gap cannot be solved by such tinkering alone. A couple of billion here and there will not move the dial. The government will be forced to break its manifesto pledge not to raise income tax, VAT or national insurance.

This already almost happened last year. Reeves dallied with similar tinkering before having to go for the increase in employer NICs, just about remaining within the government’s promise. Her other options were prey to behavioural change, meaning there was a risk that they did not yield the assumed revenue (as has come to pass on the increase in capital gains tax). Increasing income tax or broadening the scope of VAT both have an instantaneous and predictable impact.

The Labour Party has already suffered the largest percentage point drop in the opinion polls in its first year of government since John Major in 1992. It is close to falling below 20%, the level beneath which it became terminal for Liz Truss.

A sharply negative public response to a tax-raising budget means that the Budget itself could be revamped. The rebels succeeded in watering down unpopular welfare reforms. They could repeat the same trick on the Budget. It is not a given that it will pass in the form delivered by the Chancellor at the despatch box.

New Prime Minister

Except that the Budget is a confidence vote. It must be passed or the government falls, which could ultimately lead to a general election.

Usually this would be considered a centripetal force, fusing together ill-disciplined MPs who would rather not collapse the government whilst plumbing the depths in the polls. But the welfare rebellion has demonstrated the government is struggling with party management. This is not surprising given the size of the majority – there simply isn’t enough patronage to go round and make every new MP feel loved. Boris Johnson struggled with this during the pandemic, when MPs were not physically present in the Commons tea rooms and those who had only just been elected in his landslide victory were left twiddling their thumbs on social media. Labour has plenty of first-time MPs – over half of the 414 elected – and after a disappointing first year where they fear they will soon be out of a job, they will be motivated to take action. The Prime Minister only has the power of patronage if he has power; once he moves from asset to liability, nervous and disenchanted MPs sitting on small majorities will move away from him.

Such a centrifugal force can be exploited by the Prime Minister’s enemies. Angela Rayner has already let it be known she was “instrumental” in brokering some sort of deal with welfare rebels. Wes Streeting has a new speechwriter and admitted on the George Osborne/Ed Balls podcast that the government has failed to tell a “coherent story” since it was elected. The battle for the future of the Labour Party is already underway: a crisis over a Brownite v Blairite budget will suit both sides, particularly if it consumes the underloved Starmer and Reeves in the process.

It is hard to change the leader of the Labour Party, with the rules even tougher when in government. It would usually require a vote at the party conference which this year takes place from 28th September to 1st October. That is likely to be too soon for a Gilt wobble / Budget crisis. Instead, it would be easier for the heirs to the throne if Starmer were to become what the rules describe as “permanently unavailable”. Whilst designed for someone in ill health, it is not beyond the realms of creative usurper thinking that this could be used to force Starmer out.

Fiscal Crisis

Except that once Starmer is gone, the problem remains. Successive governments have tried and failed to give the UK economy escape velocity from its destructive debt/deficit dynamics. A Rayner government tacking to the left might tell a more coherent ideological story but tax-and-spend will not satisfy Gilt markets. The Labour Party will be irrevocably split and unable to pass what is required. The factions within the Labour Party can’t agree on the criteria under which a disabled person should receive a personal independence payment, let alone big decisions on overall government spending or tax.

The Truss episode will look like a lesson in smooth crisis management by comparison.

The Bank of England cannot easily intervene to resolve the problem because a rational repricing will be underway. Their role as Market Maker of Last Resort can reduce market dysfunction but they would be in an invidious position if left to intervene in Gilt markets whilst politicians failed to take the medicine. Propping up bad policy would undermine their credibility.

The Bank is already preparing its toolkit, having recently conducted a System-Wide Exploratory Scenario (SWES) where around 50 financial firms modelled their responses to a specific market shock. This exercise identified two potential areas of tension: the Gilt repo market and the sterling corporate bond market.

- To mitigate issues in the former the Bank of England has created the Contingent NBFI Repo Facility which would enable eligible insurers, pension and LDI funds to borrow cash against Gilts in times of market stress.

- For the latter, nothing has yet been put into place, raising the risk of what the Bank terms a ‘jump to illiquidity’ in sterling corporate bonds ‘reducing its effectiveness as a source of financing for the real economy’.

The Bank is evidently aware of the risks. The new Gilt repo facility is only envisaged to offer a term of 1-2 weeks, indicating it would only take the immediate sting out of any selling pressure and couldn’t be extended indefinitely. The impairment in corporate bonds would exacerbate the deteriorating fiscal position.

In the case of a fiscal crisis the Bank cannot solve the problem, precisely because it has been caused by the fiscal authority: namely, elected politicians. The crisis will roll on until a set of politicians is elected on a mandate to solve it.

In Conclusion

- A Labour party elected with a majority but no mandate means the current government cannot please both its voters and the markets.

- The Gilt market will force the government’s hands, busting open the ideological wedge in pursuit of a fiscally coherent compromise.

- The Labour Party will not survive the process without splitting apart, ushering in a rolling fiscal crisis.

- The Bank of England can smooth volatility but cannot remove it without compromising its own hard-earned institutional credibility.

- The crisis will roll on until a new election brings a government with a majority and a mandate to solve it.

Helen Thomas CFA

CEO

E: [email protected]

M: +44 (0) 7788 751 480

Thomas Berey

Analyst